This month, Chief Conductor Jaime Martín will lead the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and musicians from the Australian National Academy of Music (ANAM) in two concerts of Stravinsky’s iconic ballet scores for The Firebird, Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. The celebrated maestro takes time out from rehearsals to talk to Limelight as he also prepares to conduct the works of Sibelius, Ravel, Dvořák, Berlioz and Tchaikovsky.

Jaime Martín. Photo courtesy of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

“I cannot tell you how happy I am,” says Jaime Martín, fresh from rehearsals with cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. “It’s such a wonderful orchestra and it’s so nice working with them, because everybody’s trying to make everything so comfortable and feel very free. That’s exactly what you want when you conduct – to feel free to try things out; to experiment with sounds and colours.”

Such experimentation was what Igor Stravinsky aimed for when he wrote The Firebird, Petrushka and The Rite of Spring for impresario Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes between 1910 and 1913. Martín is currently leading the MSO in a series of concerts that will culminate in a bold program combining all three ballet scores.

“One of the things I wanted to try during these few weeks is to go through completely different styles of music. Today we were rehearsing Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No 2 with Sheku and he is fabulous. It’s his first experience with an Australian orchestra and an Australian audience.”

“We also rehearsed Dvořák’s Symphony No 9 From the New World. It’s like a festival of all the sounds you can make … and then with Stravinsky we have a festival of many other things, not only colour but the freedoms found in The Firebird, Petrushka and The Rite of Spring.”

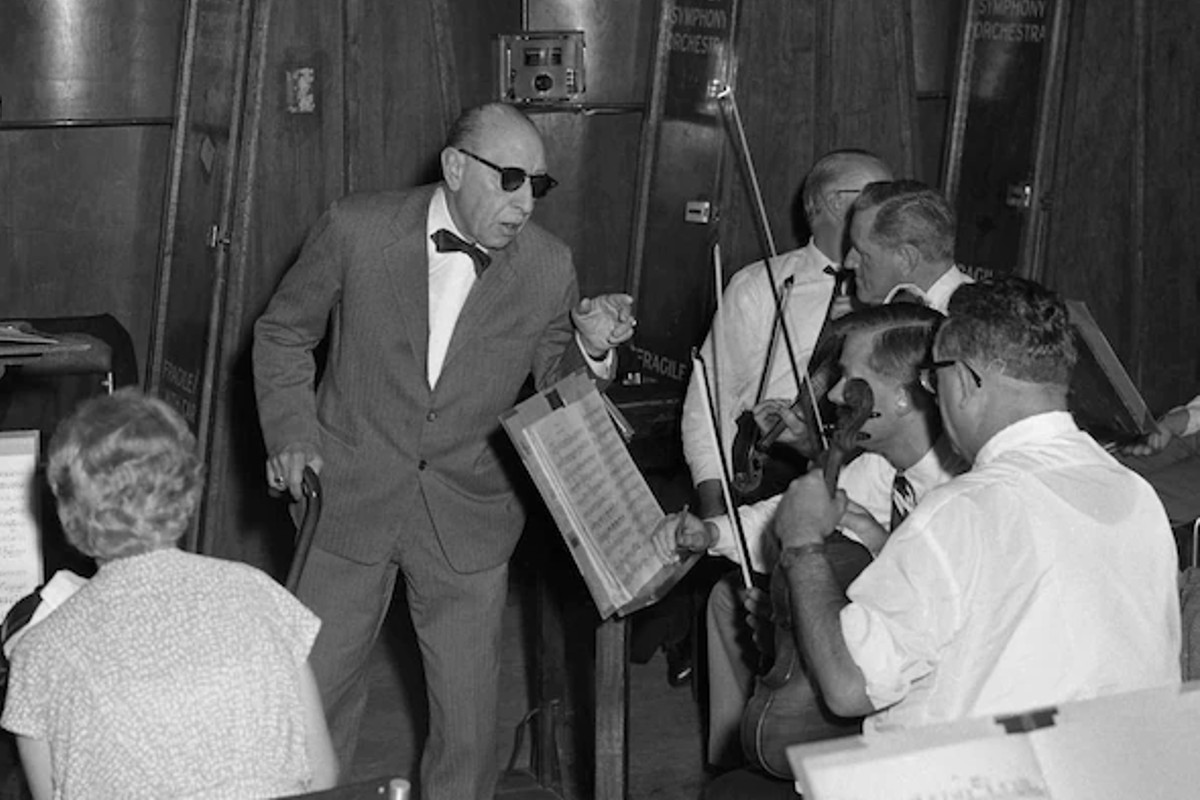

In 1961, at the age of 79, Stravinsky visited Australia and led the MSO in a performance of his 1928 ballet score Le baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss). For this upcoming concert, Martín considers the composer’s three earlier ballets as the obvious choice to represent the period in which he wrote for Diaghilev in Paris.

Martín says, “I performed them as a flute player in concert with the Mariinsky Orchestra, and I had such a good time that I thought it would be nice to put this project together. I’m really looking forward to it and it’ll be hard work for the orchestra, but everyone’s excited about it.”

“Petrushka is such an amazing piece,” Martín says, “and very demanding for the orchestra in a completely different way to The Rite of Spring. Of course, The Firebird is the most lyrical of the three. It’s the earliest one and the piece that brought Stravinsky to work for Diaghilev for the first time. You can see Stravinsky’s evolution through these three works from the most melodic – there’s lots of themes and melodies in The Firebird – to the completely experimental, rhythmical patterns in Petrushka and finally The Rite of Spring. That’s a completely crazy piece. It’s extraordinary to think that, although we consider The Rite as the beginning of the future for Stravinksy, it’s actually as far as he went. Afterwards he started writing in a much more a neoclassical style.”

Does Martín see a difference between conducting ballet scores and works written to be performed in concert?

“I feel that more with The Firebird. There is music in the complete version we are going to play, during which you can tell something should be happening on the stage and the music is basically accompanying it. That’s why Stravinsky himself made the three different orchestral suites of the ballet, which are basically a bit shorter and take away these transitional moments. But this only happens in The Firebird. He never cut The Rite of Spring or Petrushka.”

Martín adds, “The only thing he did in Petrushka was create an alternative ending for concerts, so rather than finishing soft, it finishes loud. But we are going to use the original ballet ending. If we would have done it on its own, with Ravel’s Piano Concerto in the first half, then we’d finish with Petrushka and use the orchestral ending. But in the context of the three ballets, I wanted to present them as they were intended. Petrushka is the second piece anyway, so we don’t need to have an apotheotic ending at that moment.”

“I think Stravinsky changed the ending for the concert, because he wanted the audience to clap louder,” says Martín, laughing.

When conducting a piece originally intended for the stage, what goes through Martín’s mind when he first studies a score like The Firebird?

“As a flute player, I can’t remember how many times I have played The Firebird. But as a conductor, when I start working on a piece like that, the first thing I always try to do is read as much as possible about the context; what was happening in the composer’s life at that time it was written; and what the story is about. I try to go through all Stravinsky’s descriptions of what happens in each moment. It’s very important for me as a conductor to visualise that and explain it to the orchestra.”

Igor Stravinsky during his 1961 visit to Australia. Photo © ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

“Then the most important part is to try to understand the score as much as possible; the dynamic relationship between the instruments and how they interact. Stravinsky is a complete genius in the way he uses the instruments. Look at the opening of The Rite of Spring. He uses the bassoon in a register that was almost science fiction at the time – it was so high. If he would have given this solo to an English horn, for instance, it would have sounded very comfortable with more or less the same kind of colour, but it would have sounded too easy. He wanted the opening to sound difficult; he wanted it to sound dangerous! Nowadays, bassoon players are used to this and prepared for it, but at the time it premiered, the bassoon players didn’t know what to do and they had to find new fingering. That’s the genius of Stravinsky – he not only finds the colour of the instruments, but he knows when they are in trouble. And sometimes he wants to create that trouble. He wants the person playing to feel uncomfortable. And he manages very successfully.”

When The Rite of Spring first premiered in 1913, it wasn’t only the musicians who felt uncomfortable. Many in the audience were outraged too. Martín believes that could have been the result of clever marketing on Diaghilev’s part.

“People walked out, but I think the hype around that premiere was almost provoked. Very soon after it was a big success. Maybe the reaction attracted people’s curiosity, or it could be they went in support. There are even theories that some of the scandal was paid for by Diaghilev.”

“Sometimes audiences need time to get familiar with a piece of music. It’s hard to believe now, but Brahms’ First Piano Concerto was hated by the audience when it premiered. Beethoven’s Symphony No 5 was not particularly well received either; nor was ‘Eroica’, which they thought was too long. So, I think sometimes you need to listen to something twice, which is what Schoenberg did with his Second Viennese School after the war. The format for their concerts meant that each new piece was performed twice, to give the audience the chance to understand it better. Maybe that was a good idea.”

Has performing in an orchestra enabled Martín to better understand Stravinsky’s ballet scores?

“It makes you realise the problems a piece has inside the orchestra. I used to be the Principal Flute of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and before that the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. Being in the middle of the orchestra and playing a piece like Petrushka makes you realise that the bit between the oboes and the horns is difficult, because the oboes have triplets and the horns have semiquavers, but how does it all fit? I think one of the most important qualities for an orchestra player is not to worry so much about what you play, but to be aware of what everybody else is playing. And, for me, this has been invaluable training to be a conductor. Now when I’m conducting, I try to help the musicians put things together. If people can hear each other, it’s much easier than if they have to just rely on the beat from the conductor.”

Is it possible to set a benchmark as a conductor?

“I really hope that each performance is a bit different. If I did a piece today, it wouldn’t be the same as when I did it a month ago. Life affects the way you are, and the way you are affects the way you perform music. In his memoirs, Karajan writes how surprised he was to find that thinking about tempi at his house in the Alps was completely different to when he went back to Berlin. The altitude made him feel the tempi differently, because his heart was beating at a different speed.”

How then does Martín judge a good performance?

“When you’re conducting it’s very difficult, because you’re anticipating the music. When I was already conducting, the Chamber Orchestra of Europe asked me to play in Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony at the Barbican, because the Principal Flute was ill. Bernard Haitink was conducting and afterwards I was in the lift with him. I said, “Bernard, that was wonderful. Did you enjoy it?’ And he replied, ‘Jaime, you’re a conductor now. You should know better. I don’t know if it was good … I was only the conductor!’”

Jaime Martín conducts the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in Symphony in a Day on 5–6 August, Stravinsky’s Ballets on 12–13 August, Poetry in Music on 19 August, and Sibelius & Ravel on 25–27 August. More information about what’s on can be found here.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.