Yawulyu (in Warlpiri, awely in Anmatyerr) is a genre of song performed by many groups of Aboriginal women across a broad area of the Central Australia. Each yawulyu is sung as a series of many short verses with accompanying dances or other actions such as body painting and the placement of ceremonial items. Each verse refers to a particular place, ancestor or action that the ancestor performed. Yawulyu is performed at community events, inter-cultural festivals, family camp-outs and at annual initiation ceremonies. In the past yawulyu was also a frequent evening activity as different groups gathered for social and economic reasons, sharing songs that celebrated the practices that sustained everyday life. Today, as always, performing these ceremonies cultivates a sense of place and emotional connections with land and biota, a worldview and knowledge that is increasingly under threat from the pressures of the modern world.

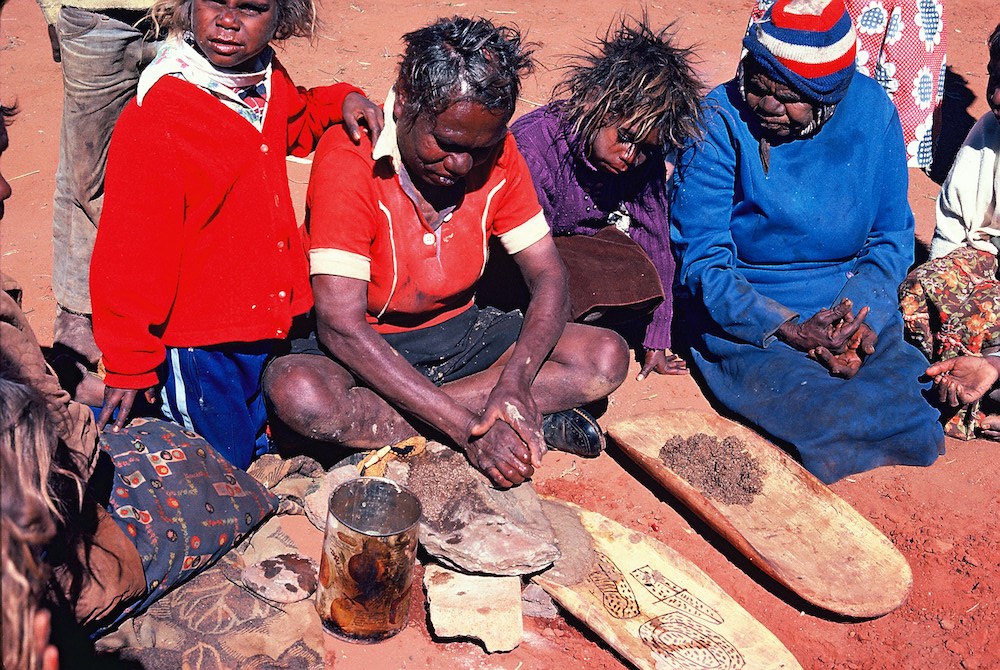

Judy Nampijinpa Granites grinding seeds and preparing pirrdijirdi dampers. Photo © Mary Laughren

Judy Nampijinpa Granites grinding seeds and preparing pirrdijirdi dampers. Photo © Mary Laughren

The first night that I spent in the Warlpiri community of Yuendumu, over 13 years ago, a group of elderly women had gathered in a cleared ceremony ground to the west of the community area. I was invited to come along and soon learned that they planned to sing and dance until sunrise the next morning – for the last time formally mourning a much-loved senior woman who had passed away a few years earlier. On this night, the women were to perform the yawulyu that were owned by the deceased and her sisters, many of whom were present, opening up these songs so that they could be performed again in public ceremonies. As the sun began to set, creating the fuzzy light which I soon came to know typified desert evenings, I dragged my swag out of the car and joined it to one of the long rows of bedding along which around fifty women had already gathered. I was easily overwhelmed by the beauty of songs, the body paintings on the women’s breasts and upper arms, the dances and the power of and respect for the kuturu – two ritual poles standing in the centre of the cleared area that were material representations of the focal Dreaming ancestors. At sunrise, this performance culminated in an intense exchange of blankets and other valued goods. As I found myself once again back in normal life, I was left reflecting on the power of this musical tradition as well as its fragility in the modern world, only being known by this small group of elderly women.

Over the next few years, I worked as a PhD student alongside Warlpiri elders to record and document many different genres of Warlpiri song. This research was part of the Australian Research Council Linkage project ‘Warlpiri Songlines: Anthropological, Linguistic and Indigenous perspectives’ (2005 – 2007) which was a partnership between the Australian National University, the University of Queensland, the Central Land Council and the Warlpiri Janganpa Association, who contributed funds from royalties they received for mining on Warlpiri country. Chief investigators of this project, Nicolas Peterson, Mary Laughren and Stephen Wild, all had long histories and relationships with Warlpiri people from their research over many decades. In my role, I worked alongside two key Warlpiri collaborators, husband and wife, Thomas Jangala Rice and Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan (sadly now deceased) as well as many different groups of elders. Most days, Jeannie and I would sit with groups of female owners, recording many different yawulyu, and documenting additional details of the song words, the associated Dreaming stories and the country. As these stories and songs are commonly focused around the long ancestral travels across country, ceremonial song-sets have become known more commonly as ‘songlines’ in Australian English, reflecting the tendency for the places and events to be sung about in a particular order. While these songs do follow the general sequence of the Dreaming travels, there is flexibility in the precise order of presentation of songs surrounding a particular place, and singers regularly foster particular connections through selection of particular verses in individual performances.

Edible seeds in a coolamon. Photo © Mary Laughren

Edible seeds in a coolamon. Photo © Mary Laughren

In 2016, with colleagues Linda Barwick and Myfany Turpin at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, I began working on a new ARC Linkage project ‘Vitality and Change in Warlpiri Songs’ (2016-2019), alongside anthropologist, Nicolas Peterson from the Australian National University and Yuendumu-based PAW Media and Communications, and Kurra Aboriginal Corporation (again contributing royalty money for this project). Centred on utilising archived recordings and documentation to revitalise Warlpiri songs in their contemporary contexts, our project draws on a rich legacy of research in Warlpiri communities. Linda and Myf had also spent many years working with Aboriginal people across Central Australia. Recently, we began drawing together recordings and documentation that we have separately made with women from various communities to the north-west of Alice Springs and which commonly focus on Dreaming stories relating to different types of edible seeds, their harvest and production.

In the mid-1990s Linda had worked with a group of Warlpiri women living in the community of Alekerenge where she recorded two different sets of Ngurlu ‘edible seed’ yawulyu relating to the sites Jipiranpa and Pawurrinji. Years later she worked with senior owner for these songs, Fanny Napurrurla Walker, and linguist Mary Laughren to transcribe the song words and document associated stories. Myf had worked with Warlpiri and Anmatyerr women from the communities of Willowra and Ti-Tree on two yawulyu song sets relating to different edible seeds: one centred on the country at Arrwek, an area known in English as Brooke’s Soak just to the east of Yuendumu, and the other the Watiyawarnu ‘Acacia tenuissima’ Dreaming that travels from Pawu ‘Mt Barkly’ near Willowra. The Warlpiri women who I worked with in Yuendumu, explained that the Ngurlu ‘seed’ yawulyu that we had recorded in 2006 joined country with the set of songs from Jipiranpa (as documented in Linda’s recordings). Similarly, with the Watiyawarnu yawulyu the Yuendumu women explained that they ‘take over’ the singing at the site of Ngurlu-lirri-nyinanya where the Willowra women had finished. These sets of songs sung by different groups of women across broad areas of the desert are showing how they identify individually with different sections of these song sets about edible seeds, yet also share important interrelationships with women from more distant country.

Mona Napurrurla Poulson and Peggy Napurrurla Poulson dancing as two lukarrara (desert fringe rush) ancestors. Photo © Mary Laughren

Mona Napurrurla Poulson and Peggy Napurrurla Poulson dancing as two lukarrara (desert fringe rush) ancestors. Photo © Mary Laughren

The content of these songs centres on seed collection and harvest, once important for subsistence, and still vital to Warlpiri and Anmatyerr women’s identities and links to country. Whilst seed collection, cleaning and food production would have once dominated Aboriginal women’s work, nowadays with the introduction of white flours and bread, these activities are no longer commonly practiced. Many younger women no longer know how to identify plants, nor have the practical skills required for the arduous tasks of harvesting, winnowing, and grinding these seeds in to their edible form. Ethno-ecologist, and co-researcher, Fiona Walsh, has contributed video-documentation of the techniques used for harvesting, winnowing clean (in the wind) and grinding seeds to flour. These Warlpiri yawulyu songs represent an aspect of Australia’s deep history alluded to by Bruce Pascoe in Dark Emu (2014), when he recounts the journals of early colonists who write of the auditory dominance of the sound of hundreds of women threshing wattle plants and the intensity of the aroma of fields full of harvested plants. The oldest grindstone with residue of ground seeds, is found in Arnhem Land and dates to 65 000 BP, suggesting that Aboriginal women have been harvesting and producing seeds for time periods of deep historical significance. In Central Australia, archaeological evidence shows that there was an intensified period of seed gathering and production techniques over the last 3000 – 4000 years.

Warlpiri women singers and dancers stand in a long line in preparation for yawulyu rituals performed at the Yuendumu Women’s Museum. (Left to right) Judy Nampijipna Granites, Dolly Nampijinpa Granites, Kurnngarri Nangala, Mary Nungarrayi Robertson (Ngarlinjiya), Yimarla Nangala, Pirrkiriya Nangala Spencer, Jeannie Nangala (Kamilypa), Maggie Nampijinpa Ross, Molly Nampijinpa Langdon, Mary Wakukuta Nangala, Winnie Nangala Ross, Tilo Nangala Jurrah, Lucy Nakamarra White, Maggie Napurrurla Poulson, Long Maggie Nakamarra White and unknown. Photo © Mary Laughren

Warlpiri women singers and dancers stand in a long line in preparation for yawulyu rituals performed at the Yuendumu Women’s Museum. (Left to right) Judy Nampijipna Granites, Dolly Nampijinpa Granites, Kurnngarri Nangala, Mary Nungarrayi Robertson (Ngarlinjiya), Yimarla Nangala, Pirrkiriya Nangala Spencer, Jeannie Nangala (Kamilypa), Maggie Nampijinpa Ross, Molly Nampijinpa Langdon, Mary Wakukuta Nangala, Winnie Nangala Ross, Tilo Nangala Jurrah, Lucy Nakamarra White, Maggie Napurrurla Poulson, Long Maggie Nakamarra White and unknown. Photo © Mary Laughren

Warlpiri and Anmatyerr women’s yawulyu song sets are nowadays known only by a dwindling group of elderly women yet capture many of the details of complex preparation methods, links between groups of women across the desert country and detailed ecological and ethnobiological knowledge. In the exhibition currently displayed at the Sydney Conservatorium library, we present some of the materials from this research project with interactive audio and video links to individual song verses, photographs of dancing and body paintings, associated artwork and some of the actual seeds focal to the songs. Additionally, University of Sydney ecologist Glenda Wardle has contributed a poster on the lifecycle of spinifex seeds in the deserts of Australia. The interdisciplinary approach to this research illustrates how Aboriginal musical traditions must be holistically appreciated and understood as they hold on to multifaceted forms of knowledge and practices.

Georgia Curran is a Research Associate, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, The University of Sydney. The research exhibition Songs of Seeds and Seeds of Songs: Warlpiri and Anmatyerr women’s songs is displayed at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music library until October 6

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.