Time has an echo which rings loudest from a century back. That trailing history is a mirror that reveals the present to us through the stories of the past. In 2018 we are faced with the anniversary of the end of the Great War and the lessons it can teach us about how, one day, we might achieve a lasting peace. The failure of the League of Nations to prevent the Second World War is well known but less known is Australia’s original ambivalence to this collective security organisation.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes was a deep sceptic of the League and the international liberalism it embodied. He was also a vocal opponent of the proposal of a clause guaranteeing racial equality put forward for consideration at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference by Japan for inclusion in the League’s charter. According to Hughes, “ninety-five out of one hundred Australians rejected the very idea of (racial) equality” and that “no Government could live for a day in Australia if it tampered with the idea of a White Australia (policy)”. The rejection of the Racial Equality Clause offended Japan, arguably fuelling the expansionism which led to the War in China and the Pacific.

The Kiss by Gustav Klimt

The Kiss by Gustav Klimt

In contrast, Robert Schuman, the architect of the European Union, spoke while fighting with the French Resistance about the need for increased Franco-German (and European) reconciliation once hostilities were ended. After the Second World War, he devised the European Coal and Steel Community which meant no European country could create armaments without the permission and knowledge of the greater whole. In 1949, after the creation of NATO, he said, “we are carrying out a great experiment, the fulfilment of the same recurrent dream that for ten centuries has revisited the peoples of Europe: creating between them an organisation that puts an end to war and guarantees an eternal peace… Our century, which has witnessed the catastrophes resulting in the unending clash of nationalities, must attempt and succeed in reconciling nations in a supranational association.” This entity, the European Union, remains humanity’s most enlightened response to war and is today under threat from extreme right and ultra-nationalist parties and agendas.

Those most directly affected by war are women, children, the aged, and also artists. The Arts is an industry which can only thrive when a healthy economy affords the luxury of creating beauty. The great flowering of European culture prior to World War I was financed by a vast wave of economic development which allowed for state and private commissioning of art and music – that sense of affluence was destroyed by the cost of the war and the subsequent Depression. Therefore on the centenary of the end of WWI, the Flowers of War is presenting on August 10 and 11 at the National Gallery of Australia, in partnership with the EU Delegation and the Austrian and Portuguese Embassies, an overview of the cultural cost of the Great War to show exactly what price Europe measured solely in terms of artistic loss. The program, entitled, The Lost Jewels, is a statement of support for the aims of the EU and its role in normalising relations through diplomatic means.

Each European culture suffered devastating but different losses – in Germanic cultures, it would be the death of a great new wave of painters. In 1918, Austria lost both Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele – a towering master and his most talented protégé – to the great pandemic, the Spanish Flu. One theory is that the flu virus crossed from pigs to humans at the enormous Etaples military base in Northern France sometime in 1917, and was carried by the 100,000 Allied troops who passed through there, to the world. It killed many more times the total military losses of the war, and estimates which include Asian losses, range as high as 80 to 100 million deaths (or between three to five percent of the world’s population) – as many people in one year as the Black Plague killed in a century. Klimt, dying at the peak of his powers, left behind a slew of unfinished portraits (which will feature in the concert) which speak to the free and constant flow of masterworks that were coming from his brush at the time of his death. Adding insult to injury, more than 14 of his late masterpieces were destroyed by the retreating SS forces when they dynamited Immendorf Castle in May 1945, including his vast series of paintings for Vienna University which had been placed in the castle for safekeeping. They now live only as black and white insurance photographs.

Death and the Maiden by Egon Schiele

Death and the Maiden by Egon Schiele

Egon Schiele, in contrast, was the firebrand who would have changed the Austrian art world, and probably did anyway, even though he only lived to 28. Known now mainly for his provocative nude portraits, often highly sexualised, he was also a gifted landscape painter. His art is strikingly modern, often very minimal, and features a potency of line which powerfully reveals the inner life of his subjects, clearly influencing subsequent generations of artists throughout the last century.

For Germany the loss would be even crueller. Since the time of JS Bach, German culture had focused its gaze squarely on music – their only truly great painter prior to WWI being Caspar David Friedrich (1774 – 1840). However with the advent of the Blue Rider group in Munich, led by Franz Marc, August Macke and featuring young talented painters such as Wilhelm Morgner, and the Die Brücke (The Bridge) group from Dresden, German pre-war art finally began to display work that might have in time challenged the global dominance of the French impressionists. However within a year of the war’s declaration that magnificent outpouring of exuberant colour was violently extinguished. August Macke was killed in 1915, with Franz Marc falling at Verdun a year later in 1916. Wilhelm Morgner, who had served from the first day of the war, would finally be killed in the Third Battle of Ypres, being buried in Langemark cemetery along more than 44,000 other German soldiers in one of the largest military cemeteries in the world. Additionally the other German artists who served and survived, Otto Dix (1891 – 1969), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880 –1938), Max Ernst (1891 – 1976) and Max Beckmann (1884 – 1950) all produced in the post-war period some of the most harrowing and bleak images ever recorded. Otto Dix’s black and white etchings from his series Das Krieg (The War), populated by gas-masked grenade-throwing Stormtroopers and maggot-infested skulls, remain the most nightmarish images of the 20th century. Such was the trauma of both wars, colour would rarely return again to Germany’s art world.

France, the country of the world’s great painters, conversely lost its greatest composers, many of whom did not even serve in the war. With their deaths, the great wave of musical impressionism came to an end, and with that, Paris lost its role as the capital for premiering new works such as Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. The first composer to be lost was Albéric Magnard, the “French Bruckner”, who became a national hero in 1914, when he fired on the invading German soldiers who had trespassed on his land. He killed one of them, and was killed when in return they set his house on fire, destroying his unpublished scores as well.

Claude Debussy was at the height of his compositional powers when the war broke out, and was considered France’s most famous composer, played the world over. He had been diagnosed with colorectal cancer and in 1915 underwent one of the earliest colostomy operations which caused him enormous pain and suffering for his remaining three years. His last masterworks works were chamber works including an unfinished series of sonatas (for violin and piano; cello and piano; and flute, viola and harp) which are amongst his most played works. After he died at home on March 25, 1918, his funeral procession made its way through the deserted streets of Paris as German artillery bombarded the city.

Lili Boulanger

Lili Boulanger

Lili Boulanger, the first female winner of the Prix de Rome composition prize, would die ten days before Debussy on March 15, 1918, most likely from Crohn’s disease. Her death was an incalculable loss for female composers, as she was the most likely to have broken through to achieve international fame, had she enjoyed a normal lifespan. This was made worse by the fact that she, and her sister Nadia (who would later become a famous composition teacher), spent the war and Lili’s precious time and energy organising efforts to support French soldiers, in particular those musicians from the Paris Conservatoire who signed up and died in droves. Dead by 24, she remains the youngest composer to have entered the classical canon. In comparison, the catalogues of Pergolesi who died at 26, Schubert who died at 31 and Mozart who died at 35, do not contain the breadth of quality as hers, if we cut them off at the same age. Only very recently have female composers such as Elena Kats-Chernin, Kaija Saariaho, Jennifer Higdon and Sofia Gubaidulina finally broken through the glass ceiling internationally. With Debussy’s and Boulanger’s deaths, the greatest male and female composers in France were lost, and Maurice Ravel, who was closest in talent to Debussy, had his health ruined by his service as a truck driver during the war, only producing 15 works in his remaining 19 years of life following the Armistice, compared to 66 works written in the 26 years prior to the war. With the Great War, French music lost its global prominence and has never regained that standing since.

Spain and Portugal were similarly impoverished. Spain’s most famous composer, Enrique Granados (1867 – 1916) had premiered in 1911 his suite for piano, Goyescas, based on paintings of Francisco Goya, to enormous success. Emboldened by its popularity he expanded the material into an opera of the same name. The outbreak of war caused its European premiere to be cancelled, and Granados was deeply relieved when the Metropolitan Opera chose to premiere it instead in New York City on January 28, 1916, where it was rapturously received. In the afterglow of the opera’s success, he was invited to perform for President Woodrow Wilson and also to record Goyescas on player piano music rolls for New York’s Aeolian Company. Having delayed his return and missed his boat back to Spain, he instead sailed to England and then crossed the channel on the passenger ferry, SS Sussex, which was subsequently torpedoed by a German U-boat. Evacuated to a lifeboat, he heard his wife, who had become separated from him in the panic, calling out, and he dived in to the sea, despite his life-long phobia of water, and subsequently drowned alongside her. He was 49 years old and on the verge of international fame.

While Spain lost its master, Portugal would lose its greatest young talent, António Fragoso. Born in 1897, he studied composition and piano at the Lisbon Conservatoire, where he began studying at the age of 17. He graduated on July 3, 1918, dying two months later on October 13 from the Spanish Flu, aged 21, along with 138,000 other Portuguese citizens that year. He left behind a handful of works which clearly show his promise. One of which, his Nocturne, a famous piece in Portugal, reveals an individual and assured compositional voice. Portugal with its small population of six million, similar to Belgium and New Zealand who lost the young composers André Devaere and Willie Braithwaite Manson respectively, would not be able to produce another great composer to replace him.

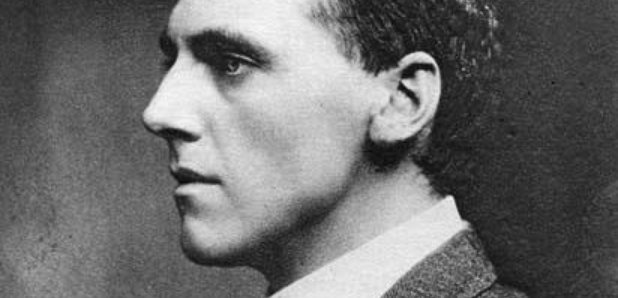

Frederick Septimus Kelly

Frederick Septimus Kelly

Australia in turn lost its composer, Frederick Septimus Kelly, in the Somme in 1916 at the age of 35. A notable pianist as well as a gold medal winning Olympic rower, his works remain largely unknown, even though his catalogue is equivalent in scale and quality to Ralph Vaughan Williams’ catalogue at the same age. Kelly will gradually come to be re-evaluated through the recordings currently being produced by the Flowers of War. While not able to rival his fellow student Percy Grainger for verve and sheer innovation, his works are more accomplished technically and display an individual voice of great sensibility. His most famous work written in the trenches at Gallipoli, the Elegy for Rupert Brooke, with whom he served, has become an acknowledged international masterwork. His Symphony (entitled Suite in E flat) will be released in 2019 by the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra. As this and his string trio, also recently recorded and soon to be arranged for string orchestra, and his virtuosic piano works (some of the earliest such works written by an Australian and also recently recorded) become performed more and more in the coming years, it will become clearer just what level of talent we lost.

Beauty is a flower that is only appears when societies are stable, wealthy and flourishing. Its enemy is war, which like a hard frost, burns deep, destroying all blossoms, often forever. The Great War wounded Beauty to such a degree it took almost a century to recover from the trauma. Classical music remains frozen even to this day in a largely pre-WWI repertoire, the grieving population having turned its back on modernism’s cathartic post-war creations. Only recently have contemporary composers been allowed to return to unself-conscious uses of melody and harmony, and to the expression of beauty for its own sake. Artists should learn to use their talents to empower diplomacy, for only through global stability will we enjoy the chance to create and thrive. This is the intention of The Lost Jewels program, to show through the cultural losses of 12 countries that past enemies are now, a century later, through the European Union and global diplomacy, working as joint architects to build a lasting peace.

The program will close with Lili Boulanger’s great masterwork, her Old Buddhist Prayer, written between 1914 and 1917, and first played in 1921, three years after her death at the age of 24. The words are: let everything that breathes – let all creatures everywhere, all the women, all the men, those of every skin and colour, let all those beings exist without enemies, without obstacles, overcoming their grief and attaining happiness, able to move freely, each in the path destined for them.

Her final “lost jewel”, is a profound artistic response to war, speaking clearly to us from a century past, and remains as movingly relevant today as ever.

The National Gallery of Australia presents a Flowers of War concert, The Lost Jewels – Masters and Masterworks Lost in the Great War, in its James O Fairfax Theatre on August 10 and 11. Featuring music and art by creative artists from 12 European nations who died during WWI, it is directed by Christopher Latham, artist-in-residence at the Australian War Memorial, and performed by soprano Louise Page, pianist Edward Neeman, the Sculthorpe String Quartet, and the Luminescence Chamber Choir

TICKETS

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.