The Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s 2022 concert season draws to a close with Holst’s stirring The Planets. We look to the heavens to explore Holst’s inspirations, and why this work resonates so deeply with listeners.

On March 5, 1913, a 38-year-old music schoolmaster wrote to a friend about the premiere of his latest composition, The Cloud Messenger: “The Cloud did not go well and the whole thing has been a blow to me. I’m fed up with music, especially my own.” The sentiments were expressed by a man unable to find favour in a rapidly shifting musical zeitgeist: Schoenberg’s atonal revolt had turned the landscape on its head, and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring was only months away from causing an aesthetic cataclysm in Paris.

Seven years later, The Sunday Times critic Ernest Newman declared the schoolmaster to be “one of the subtlest and original minds of our time.” He was referring to Gustav Holst, following the premiere of his orchestral suite The Planets.

What is The Planets really all about and how did this once-insecure schoolmaster manage to produce a work of such lasting significance?

It was while holidaying in Spain in 1913 with essayist Clifford Bax (brother of composer Arnold) that Holst became attracted to the study of astrology. Holst’s fascination with alternative beliefs had been brewing for years: a prior trip to Algeria had kindled an interest in Eastern religions. “I am quite at home here,” he wrote to his wife, Isobel. His daughter, Imogen, suggested the Algerian experience sparked an esoteric spiritual journey. “Life there was full of unexpected happenings,” she wrote in her 1938 biography of her father. “He listened to an Arab musician play the same short phrase on his flute for hour after hour.”

British music filmmaker Tony Palmer agrees, believing Holst’s exotic travels expanded his views on music.

He was a man fascinated by ideas, wanting to understand the various parts and operations of the human brain.

Tony Palmer, filmmaker

Holst was certainly unconventional: he was a vegetarian before it was popular, and promoted socialism well before it took firm root in the eastern states of Europe.

It was these idiosyncrasies that convinced Palmer that a film on Holst was needed. “I was fed up with the BBC-spun garbage,” says Palmer, referring to the wholesome depiction of the man who, it could easily be assumed, composed The Planets and nothing more. “There had to be more to him; I wanted to find out more.” Palmer’s 2011 film Holst – In the Bleak Midwinter penetrates the veil of imagery and metaphor that shrouds his music, including his most famous creation.

Holst began working on The Planets in early 1914. A misconception is that he composed the opening movement Mars, the Bringer of War in reaction to the warfare rolling across the Continent. In fact, it was pure coincidence: the last thing Holst wanted was for his music to become an ode to military vigour. Quite the contrary, as Palmer notes: “Holst feared the mechanisation of life pervading Europe in 1914”.

Holst’s working title was Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra, leading biographer Michael Short to suggest the work’s genesis was planted in his mind as early as 1912, when he witnessed a performance of Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra. Although Holst composed according to astrological characteristics, it wasn’t until late in the writing process that each movement was labelled accordingly. But why did Holst decide to model his seven-movement suite on planets in the first place?

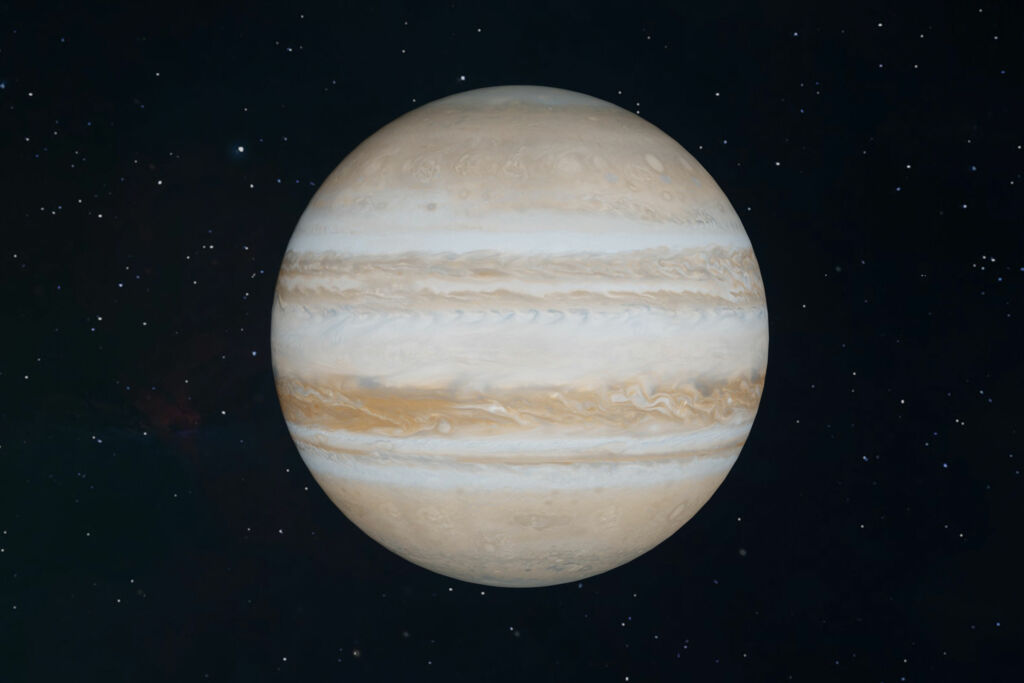

It’s important to remember that Holst composed from an astrological point of view, not an astronomical one. He declared in a letter: “The pieces were suggested by the astrological significance of the planets and not by classical mythology. Venus for instance has caused some confusion through this point. Jupiter is there as the musical embodiment of ceremonial jollity.” Historian Richard Greene explains: “When Holst chose his titles he was not indulging in the common form of program music in which a scene is depicted through sound. The few words he used for titles were meant as suggested characterisations: hints regarding what each musical movement embodied.”

Holst owned a copy of astrologer Alan Leo’s What is a Horoscope, and How Is It Cast? and used it to model his movements. In it, each planet’s characterisations are detailed. “Mars becomes ruler over fate and fortune,” wrote Leo, “as these persons will make much of their own fate by impulse. They are generous, confident and enterprising, fond of adventure and progress.” Holst’s music, therefore, attempts to represent each planet’s effect on the human condition which, when played in its entirety, escorts the listener on a psychological and philosophical journey, or “from the physical world to the metaphysical,” according to Greene.

One curiosity surrounding The Planets is the ordering of movements. Astrologically speaking, the order should begin with the Sun, then the Moon, followed by Mercury through to Neptune, and excluding Earth (Pluto was not discovered until 1930, and was then declassified as a planet in 2006). Holst listed Mercury in his notebook as “No 1”, suggesting intentions to initially follow an astronomical sequence. In Holst’s score, only Mars and Mercury have swapped places. This is usually regarded as a musical stratagem, allowing the forceful sonority of Mars to be juxtaposed more effectively against Venus. According to scholar Raymond Head, the sequence was carefully devised by Holst to underline his astrological agenda, by which the “unfolding experience of human life from youth to old age” can be heard.

Modern music, for the vast majority of people, was Elgar. For audiences hearing the beginning of The Planets, it’s difficult for us to sense just how extraordinarily new is must have sounded.

Stephen Johnson, music critic

British conductor Alexander Shelley says Holst’s score is intensely challenging. “It doesn’t contain the complexity of other symphonies of the day, but it is incredibly innovative in its orchestration.” Shelley acknowledges the task faced by performer and listener when considering the work as a whole: “Of course you can appreciate each movement individually – an idea not foreign to those of us who grew up with MTV! However, the real challenge is maintaining the work’s overall style and purpose throughout the sequence of movements.”

Listening to an isolated movement was initially how The Planets entered the public’s consciousness. Rather than unleash all seven movements at once, the composer performed sections over a two-year period beginning in 1918. Come the public premiere in London on 15 November, 1920, the movements had become “like old friends”, according to the critic L. Dunton Green.

Green, writing for the Arts Gazette shortly before the premiere, had witnessed a performance without the two serenest movements: Venus, the Bringer of Peace and Neptune, the Mystic. “It was an injustice,” wrote Green, “to rob Holst’s planetary system of the two stars whose soft light would have relieved the fierce glare of the five others.”

While the public adored The Planets from the moment it premiered, the critics were polarised. The Globe called it “noisy and pretentious” and The Times “a great disappointment. Elaborately contrived and painful to hear.” Others, like Newman in The Sunday Times, were convinced that Holst had finally thrust English music into the innovative realm of Stravinsky, Strauss and Schoenberg. The Outlook referred to the performance as “the most important of recent events in the concert world.”

Despite the immediate public success of The Planets, Holst struggled to recapture either critical or popular praise from then until his death in 1934. His later works furthered the innovations championed in The Planets, but were unable to inspire public acclaim. Posthumous commentary has highlighted the progressiveness of Holst’s late musical idiom, as well as its influence on the Minimalists, and many Hollywood film composers, particularly John Williams.

Perhaps an air of astrological inevitability had always hovered over Holst. Described as “solitary, aloof and remote”, Holst was born under the sign of Virgo, which is ruled by the planet Mercury. The composer’s creative modus operandi can almost be gleaned from Leo’s astrological treatise: “Mercury itself is colourless. But apart from this, Mercury gives adaptability, fertility of resource, and the ability to use the mind in various ways…” Thus Holst’s The Planets came to be.

The Sydney Symphony Orchestra presents Holst’s The Planets & Britten at the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall, 7–10 December 2022. Visit the Orchestra’s website for more information.

Seven landmark recordings

1925: Gustav Holst, London Symphony Orchestra

The composer conducts a lightning-fast performance, most probably due to studio limitations rather than any aesthetic agendum. Like Rachmaninov’s 1930s recordings of his own piano concertos, this is a priceless treasure and resource.

1945: Adrian Boult, BBC Symphony Orchestra

Boult’s rendering of Mars is both terrifying and beautiful; the orchestral force of this movement is executed perfectly. Ironically, given the date of the recording, it’s the Bringer of War movement which stands out.

1956: Leopold Stokowski, Los Angeles Philharmonic

The first version of The Planets to be captured in stereo, enabling the grandiosity of instrumentation to be heard. More than half a century later, Stokowski’s performance remains spellbinding.

1961: Herbert von Karajan, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Karajan’s 1961 recording is made all the more remarkable when compared his 1981 version with the Berlin Philharmonic – panned for noticeable tuning problems. The 1961 recording conveys a sense of charm, restraint and beauty.

1998: Len Vorster & Robert Chamberlain

Holst first created a four-hand transcription of The Planets and later a two-piano version. Vorster and Chamberlain’s recording is colourfully executed and brings to light many subtle tones often drowned in orchestral performances.

2006: Simon Rattle, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic commissioned so-called “asteroids” to go with Holst’s planets, including Pluto, the Renewer by Colin Matthews and Komarov’s Fall by Brett Dean. Although the debunking of Pluto as a planet coincided with this CD’s release, Rattle’s rendering is still a modern classic.

2015: David Robertson, Sydney Symphony Orchestra

The Sydney Symphony Orchestra is in top form with superb playing across all departments. David Robertson’s tempi and choices are spot-on and the recording quality is excellent. This SSO offering can take its place alongside the best. Read the Limelight review.

What else did Holst write?

Far from being a one-hit wonder, Holst composed a plethora of treasures that, unfortunately, languish in the shadow of The Planets. Holst’s fascination with Hinduism led him to compose much music influenced by this spiritualism. His 1908 chamber opera Savitri is based on a story from the Mahabharata and contains some of Holst’s most insightful writing. Critic Matthew Rye says that “the economy of the opera’s resources make it stand out from the gargantuism of the time, such as Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand and Strauss’s Elektra”.

His Beni Mora suite from 1909, again, harks to the Orient and laid the foundation for instrumentations that came to prominence in The Planets.

This feature was originally published in the June 2012 issue of Limelight and has been updated to coincide with Sydney Symphony Orchestra's performance.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.