The fact that Breaking Glass survives at all is a minor miracle. Sydney Chamber Opera’s staging of four works that came out of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music’s ground-breaking Composing Women Program was slated to premiere in late March. One of the many productions to fall victim to the COVID-19 crisis, performances were cancelled when Carriageworks was forced to close its doors. Thankfully, SCO had reached the staging point and was able to record the works, though the editing process, which involved marrying audio recordings to video footage has been a significant challenge. As SCO Artistic Director Jack Symonds says, “it felt like both an enormous risk and privilege to be making something out of nothing when many around us were losing hope and the world was shutting down.”

Jessica O’Donoghue in Commute. Photo © Daniel Boud

Jessica O’Donoghue in Commute. Photo © Daniel Boud

That Breaking Glass, now presented as a Facebook Premiere Event, comes across as considerably more than something out of nothing is a tribute to SCO, and especially to the talents of its four composers, all women, all Australian: Georgia Scott, Peggy Polias, Josephine Macken and Bree van Reyk. Each work has been fully realised and the performances, directed with imaginative flair by Clemence Williams and Danielle Maas, couldn’t be better. Conceptually, the four shorts (each comes in at under half an hour) are loosely bound together by ideas of survival against the odds, and while some feel a closer fit to ideas of what an opera ought to be than others, each here is given what has to be its best shot.

Opening proceedings is Her Dark Marauder by Georgia Scott. With a text by Pierce Wilcox it reimagines certain ideas expressed in the writings of Sylvia Plath, a poet who fought and lost a lifelong battle with depressive disorders. In Scott’s work, three singers (who perhaps represent a single fragmented personality) struggle to articulate their thoughts as individual creativity wrestles with an invisible enemy that can appear externally one moment and internally the next. The resulting traumatic 20 minutes is expressed in vocal lines that contort and clash in discordant disarray, words at times reduced to a gibbering Becket-like cacophony.

Jane Sheldon in Her Dark Marauder. Photo © Daniel Boud

Jane Sheldon in Her Dark Marauder. Photo © Daniel Boud

Accompanied on low piano and growling, ominous percussion, melancholy woodwind lines and jagged strings twine around the voices to create an appropriately gloomy ensemble. More cohesive spoken texts attempt to make exterior sense of interior feelings associated with “diagnosis”, “cure” and their attendant suicidal thoughts. Director Danielle Maas places her three singers – Jessica O’Donoghue, Jane Sheldon and Simon Lobelson – on mountain tops that poke their heads through a wonderfully atmospheric mist (set and costume designer Charles Davis has done a superb job throughout). With typewriters on their laps, the idea of struggling to keep one’s head above water is a memorably conveyed. Wilcox’s text is thoughtful, and Her Dark Marauder does have a vague trajectory of sorts, but it’s more meditation than music drama and as such struggles at times to justify a visual component.

More successful in that respect is Peggy Polias’s Commute, a work that cries out for a visual realisation. Ever since Joyce’s Ulysses, writers have enjoyed contemporising Homer’s Odyssey, and here Polias transmutes a Sydney journey home into a nightmare vision where Scylla and Charybdis dog the protagonist’s every step and a man might turn out to be a potential woman-eating Cyclops. It’s also a dreamscape – a sort of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, as it were – that ends with the appropriate balm of Homer’s “rosy fingered dawn”. Polias also wrote the smart, urban text, which is laced with sly references to Greek epic.

Jessica O’Donoghue in Commute. Photo © Daniel Boud

Jessica O’Donoghue in Commute. Photo © Daniel Boud

Director Clemence Williams has realised this quite brilliantly with a menacing, stop/start lighting design by Alexander Berlage and stunning projected video by AV designer David Bergman. Jessica O’Donoghue makes a memorable feminist hero, a grimly determined woman who sets her face into the storm. As she makes agonisingly slow yet certain headway, gigantic hands scuttle behind her like predatory spiders and a huge, baleful eye threatens to strip her of her humanity, all interspersed with snapshots of a pair of sinister, all-too human-sized suited and booted men. Polias’s score is colourful, imaginative, complex, yet comprehensible, driven by the pulsing rhythms of the rush hour and underpinned by a sort of fractured, streetwise blues laced with vibes, clarinet licks and a purring, jazz-inflected flute. On this showing, Polias and the theatre make for comfortable bedfellows.

The Tent, with music and text by Josephine Macken is a tougher nut to crack. The work takes its title from a clever short story by Margaret Atwood in which a writer huddling inside a paper tent doodles on the walls to keep out encroaching horrors. Here, however, we find a trio of researchers tasked with collecting the earth’s dying remnants – following an ecological catastrophe – and storing or feeding them into some kind of computer. The dramatic journey comprises the scientists’ gradual realisation of the deeper implications behind what at first was simply collecting for collecting’s sake. The music mixes a gripping electronic soundscape with the live ensemble, and is never less than involving, but with a text made up of vocalisations that suggest rather than represent words, the dramatic content remains elusive.

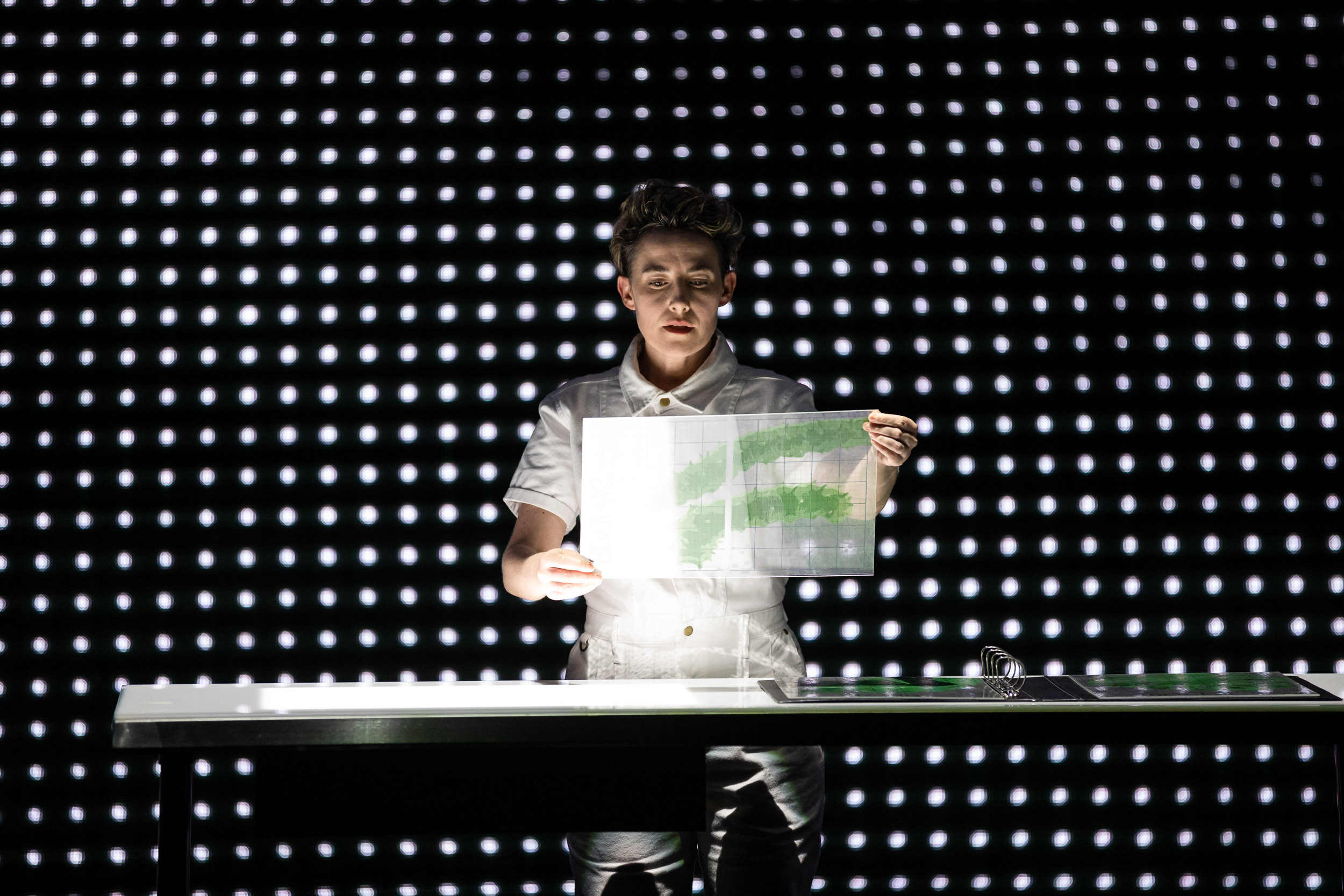

Jane Sheldon in The Tent. Photo © Daniel Boud

Jane Sheldon in The Tent. Photo © Daniel Boud

Maas’s staging looks great, and again, the set, lighting and video design is first-rate. Three singers – Sheldon, Lobelson and Mitchell Riley – clad in scientific garb stand in front of a pixelating backdrop that shimmers and pulses. Selecting objects to be curated – spore, lichen, fern, silkworm etc. – they leaf through files and the music and lighting seems to respond, though in a far from literal way. The music ranges from shifty electronica and colourful percussion to the sparer textures of the live ensemble offset by roars and growls from onstage and off, but in its current form The Tent exhibits the most tenuous of connections between music and action.

Breaking Glass concludes with Bree van Reyk’s The Invisible Bird, a bravura work that injects a welcome dose of levity into what would otherwise be an unremittingly grim evening’s entertainment. Focussing on the remarkable story of the Night Parrot – a rare Australian bird presumed extinct in 1912 only to be rediscovered 100 years later – director Clemence Williams realises it as a hilarious cabaret with capering artistes and a feather-fringed chanteuse as the ecological star turn. A subtle story of survival and man’s changing attitude toward conservation, I’m less certain it “speaks to the stifling of women’s stories” as billed, but when the performances and staging are this good, who cares?

Jessica O’Donaghue, Jane Sheldon and Mitchell Riley in The Invisible Bird. Photo © Daniel Boud

Jessica O’Donaghue, Jane Sheldon and Mitchell Riley in The Invisible Bird. Photo © Daniel Boud

Van Reyk has assembled her libretto from the scientific Latin names of endangered and extinct Australian birds and, in tandem with Williams, cleverly manages to invest such abstract material with a clear dramatic arc that leads from life, through extinction, and back to life again. Musically it’s an absolute riot, clever, funny, intricate and instantly likeable. Arranged in palindromic form, the score packs a real punch, with clattering percussion, delicious off-kilter waltzes, and reflective stretches of medieval modalism as in the haunting “extinction aria”. With a layer of witty cabaret-style choreography on top pulling such multifaceted music off is quite a feat, but thanks to magnificent performances from O’Donoghue, Riley, and especially Sheldon whose stratospheric soprano is on immaculate form as the parrot herself, it’s a tour de force. From flamboyant campery to a poignant stillness where feathers rain in a bleakly barren landscape, The Invisible Bird is the very essence of theatricality.

Leading from the piano, Jack Symonds holds his small ensemble – viola/violin James Wannan, double bass Benjamin Ward, flute Lamorna Nightingale, clarinet Jason Noble and percussion Alison Pratt – together with impressive discipline. With what feels like especially important contributions from Polias and Van Reyk, this is a major achievement and another feather in the cap of Australia’s most inspirational modern opera company.

Breaking Glass will premiere on the Carriageworks Facebook page on Saturday April 25 at 7:30pm. It can then be seen on the Carriageworks Facebook page and website

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.