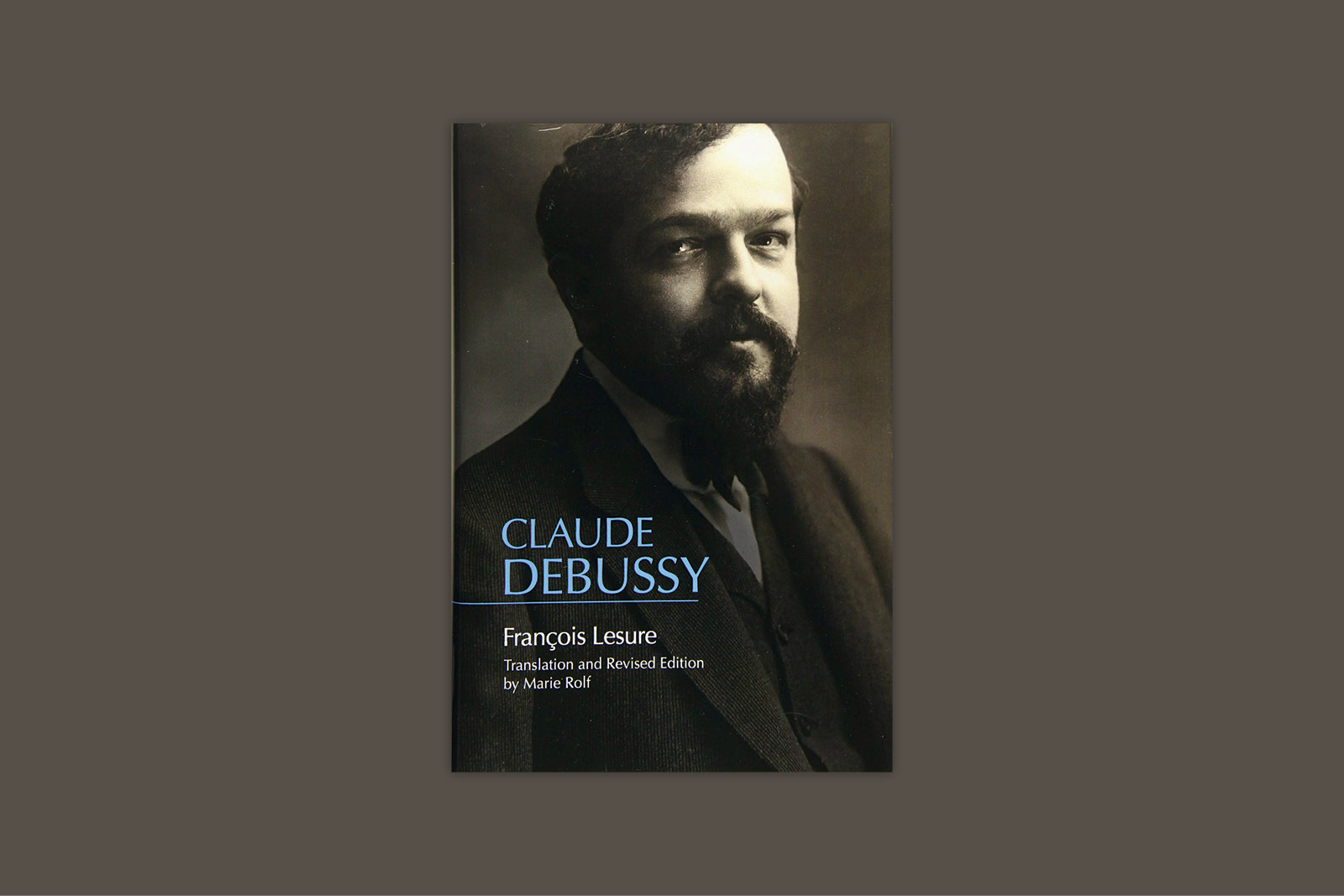

By François Lesure, Translated and revised by Marie Rolf

University of Rochester Press, HB, 544pp,

ISBN 9781580469036

Buy online from Booktopia

Claude Debussy ranks among the most colourful of musical lives. Born in 1864 to working class parents and with a father who was imprisoned for playing a part in the Paris Commune of 1870, the boy was farmed out and managed somehow to acquire sufficient skill at the piano to enter the Paris Conservatoire aged 10. An unsteady scholar, he visited Russia as a student when he was assigned a role in the itinerant family of Tchaikovsky’s patron Nadia von Meck. A born rebel, his musical philosophy took decades to formulate, during which time he became a habitué of the clubs and drinking dens of the arty elite.

A succession of passionate relationships kindled a considerable sexual appetite. He kept a long-term mistress even during an aborted engagement, his first wife attempted suicide after he ran off with the married woman who would become his second. The success of his opera Pelléas et Mélisande secured him a musical reputation as a young(ish) Turk and attracted a passionate following of young artists and music lovers, but his preference for the company of writers and painters meant he never fitted in with the musical establishment, and he was several times ostracised by Parisian society for his wayward private affairs.

Always a slow, painstaking composer, his international reputation only became assured once his ground-breaking music finally began to circulate. A late flourishing as a conductor of his own music led to a series of travels abroad, but the First World War and a drawn out and excruciating battle with rectal cancer finally put paid to a career and a life in 1918 that by rights still had much to offer.

François Lesure (1923-2001) was for many years the world authority on Debussy and his critical biography that appeared in 2003 has long been regarded as the bible for scholars, especially for those keen to gen up on the evidence Lesure assembled to debunk many of the myths that grew up around the composer and his works. This new, revised edition has been translated into English by Marie Rolf who worked closely with Lesure from the 1980s onwards. Rolf, who is currently senior associate dean of graduate studies and professor of music theory at the Eastman School of Music, has also updated Lesure to reflect the scholarly discoveries of the past 20 years, and mighty impressive it is in its range and literary clout.

Lesure and Rolf are encyclopaedic on many issues. If you want to know the exact date Debussy did such-and-such, or when each major work received its premiere in Paris, regional France, England, Russia etc., this is the place for you. The many literary movements and the figures who made up the clientele of the cafés and cabaret joints that Debussy frequented are each of them namechecked, while letters from Debussy have been widely researched providing vital information on his thoughts and motivations. And yet, at times there’s a certain dryness to the 339-page life, as if reluctant to indulge in any speculation, preferring to let the facts speak for themselves.

It’s most apparent when examining the women in Debussy’s life. The early influences of his teacher Antoinette Mauté and his vocal muse Marie Vasnier are touched upon, but the personalities remain shrouded. We know when and where his mistress Gabby and wives Lilly Texier and Emma Bardac came into his life, but little about what kept them together (or more often did not).

Compared with Stephen Walsh’s flamboyant but hyper-opinionated Debussy: A Painter in Sound that came out last year, Lesure is a bit of a plod, not helped by the 200 pages of notes, some of which add flavour, but most of which merely provide scholarly references. Walsh is also brilliant on the music, not an aspect that Lesure is keen to analyse. Anyone with a serious interest in Debussy will need this book, but don’t expect a light read.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.