To the best of my knowledge, the wind symphony is a relatively recent arrival in the musical roster of Australian music institutions. It’s a staple of American music departments, of course, where there is rarely any shortage of flautists, clarinetists or tubists, and whence there is so much repertoire. Some deal of this – many would say the best of it – derives from one Percy Aldridge Grainger, oboist and Bandsman (2nd class) in the Coast Artillery Band of the United States Army (1917-19).

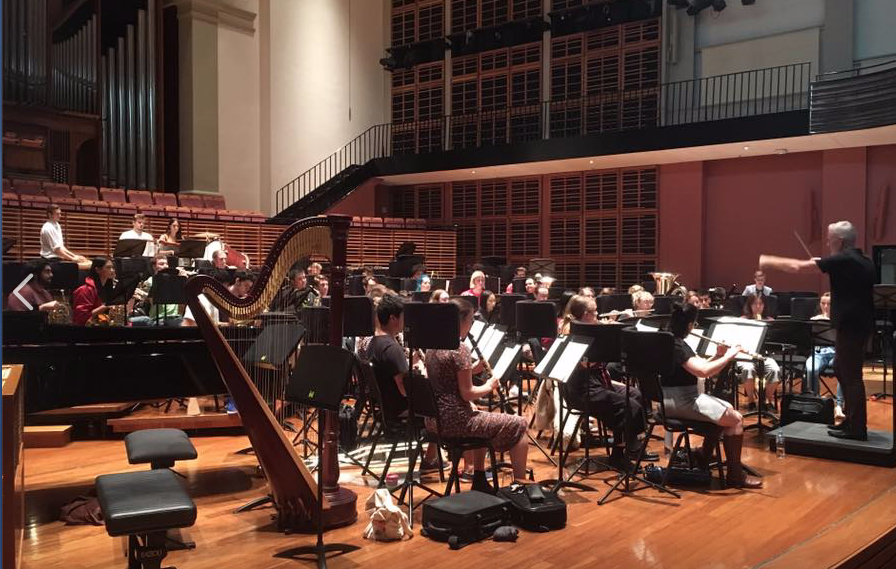

Rehearsal shot, courtesy of Jodie Blackshaw Facebook page

Rehearsal shot, courtesy of Jodie Blackshaw Facebook page

In June 2014, John Lynch arrived in Sydney to create what his official biography terms “the first comprehensive university band program in Australian history”. Previously Director of Bands at the University of Georgia in Athens, GA, and the University of Kansas in Lawrence, KS, he brought to Sydney not just decades of experience working with eager, sometimes unruly young players, but also an impressive resume as a clinician and author of books about his profession. More recently still, he has inaugurated at the Sydney Con the first graduate degree in this country in wind band conducting.

Sadly for this Grainger-Ranger, there was no Grainger in the present program. Still, there were nods backwards to Richard Strauss, the Serenade in E Flat, Op.7 (1881), one of his euphonious teenage works for small wind ensemble, and to Paul Hindemith, his mighty Symphony in B Flat (1951), from his years at Yale (1940-53).

There was a further nod to the American tradition with the inclusion of John Williams’s Tuba Concerto, composed in 1984-5 as a centenary commission from the Boston Pops. Dispensing with strings, Paul Lavender has created a new version for wind band that was premiered by Andrew Jefferies, winner of the Con’s Brass Concerto Competition last year. Jefferies, almost dwarfed by his tuba, displayed remarkable agility negotiating the outer ranges of this neglected and type-cast instrument. The closing cadenza, in particular, was astonishing, partly accompanied by two harps (two? Was this merely for balance purposes?). Good that Jefferies has another concerto in his bag now; the perennial Vaughan Williams concerto can sound somewhat shop-worn these days.

The principal attractions for this listener were the premieres of two new(ish) pieces by young Australian composers. Currently based in Brisbane where she is pursuing a PhD in composition at the University of Queensland, Cathy Likhuta, not yet 40, has already mustered an impressive array of degrees, awards and performances, here, in the USA and in the Ukraine where she studied classical and jazz piano at the Glière Music College in Kiev.

In its original 2011 version, Likhuta’s 12-minute ‘virtuosic sonata’ for alto saxophone and orchestra, Let the Darkness Out, is one of her most performed pieces. Shortly after moving to Australia in 2012, she came in contact with the extraordinary Michael Duke, since 2008 the first-ever full-time lecturer in saxophone in an Australian institution. Duke persuaded her to revise her sonata as a concerto and he was the impressive soloist in the premiere performance here, with Likhuta herself playing the jaunty, jazz-inspired piano part.

Likhuta has written an attractive, even appealing work which must surely find its way into the still small repertoire of non-American concert works for alto saxophone (perhaps she could whip up a version for string orchestra, in time for Branford Marsalis’s tour with the ACO in May?). There was a true sense of growth, as well as light and shade, without any hint of triumphalism or condescension. Duke’s masterly performance gave the work clarity and focus.

Jodie Blackshaw’s Symphony No 1 (2019) carries the subtitle Leunig’s Prayer Book, a genuflection towards those much-loved cartoons and verses of Michael Leunig, in this case four poem-prayers reflecting on the arrival of the four seasons. In terms of scope and aspiration, Blackshaw’s 25 minute symphony is a major work, inflating Leunig’s endearing line-drawings and affecting poetry to almost Mahlerian proportions.

The work teems with ideas; there is enough material here for several substantial pieces for wind band, Blackshaw’s favoured outlet for her vivid creative imagination. There is a lot of movement around the stage and into the choir-loft as soloists attempt to deliver antiphonal voices, but these are rarely given time to register the desired effect. At one stage, most of the ensemble vocalise in meaningless jabber. At another, two musicians – tenor Elias Wilson and guitarist Vladimir Gorbach – appear on stage to invoke the Reflection and Resonance on the arrival of winter and then disappear a few minutes later. There were promising solo moments, especially those for flute, soprano saxophone and trumpet, but these were never really developed in a fully satisfying way. In terms of musical construction, a composer might look more closely at the long lines of Paul Klee, perhaps less the spare meanderings of Leunig.

There is some truly glorious music in this work, especially those glistening, coruscating chords at the arrival of Spring, and a sense of growth and renewal as the score strives towards the creation of a memorable tune, via diversions into dance rhythms and gestures. On many occasions, Blackshaw’s score suggested a mix of Leonard Bernstein with the more dense textures of ‘new Romanticists,’ Americans like Jacob Druckman or John Corigliano. I found it intriguing and puzzling but, ultimately, a rewarding experience, superbly orchestrated if a little overwrought formally.

The young players – the printed program lists 60 of them – played both new pieces with a sense of identity and common purpose. It was heart-warming to see them cheering music of their own time and place. As an ensemble, they still have some way to go in terms of unison articulation and balance, but they have already produced a robust and keen texture which is gratifying. Clearly, they adore their director, John Lynch, who has been a god-send to the Con in bringing an American professionalism to the enterprise.

Less impressive though was the printed program, containing so much poorly researched, blatant claptrap and inflated biographies. This is too common in many of the music schools in this country where performance and scholarship seem to inhabit different planets. It can’t be too hard to assign budding scholars and music-writers to create program notes for live performances.

Overall, minor quibbles aside, this was an impressive evening on many counts, especially the committed and persuasive performances of the young players.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.