Louise Farrenc was, without a shadow of a doubt, a remarkable woman and a genuine pioneer. Not only was she professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire for more than 30 years, but she also achieved remarkable heights in composition in an age when so many talented female musicians were left to the confines of the salon, rather than the concert stage.

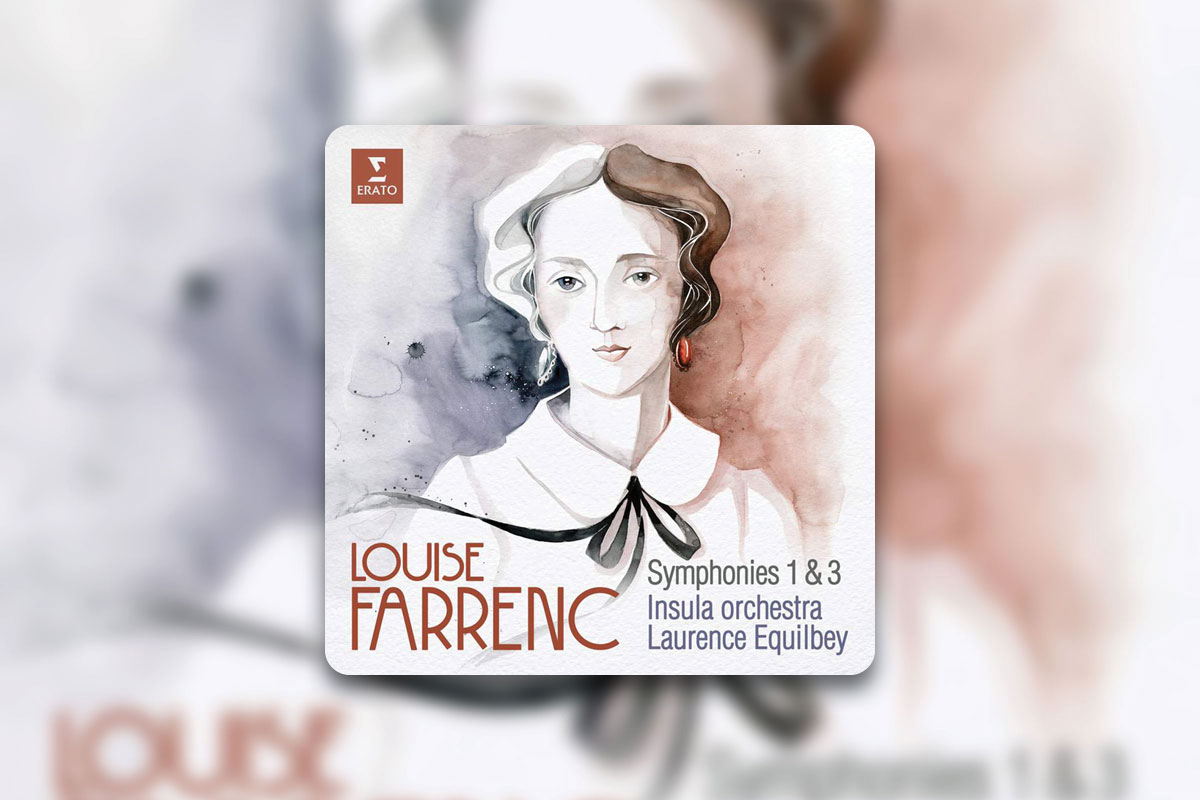

Her symphonies are fine, powerful works. Stylistically, these symphonies (both from the 1840s) broadly echo Beethoven’s symphonies, although Farrenc’s careful use of the wind section is noteworthy. The Symphony No 1 (in the very Beethovian key of C Minor) is a terrific piece of symphonic writing, and the Insula orchestra outdoes itself, rising to every powerful crescendo and diminuendo demanded by Equilbey.

For my money, though, the Symphony No 3 in G Minor is where Farrenc really shines. The piece received rave reviews upon its premiere; critic Henri Blanchard wrote at the time that “she does honour to the land of her birth with this exceptional talent, which combines a feeling for melody with the science of sounds”.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.