Such is the global phenomenon that is Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, it’s hard to remember that until Ron Chernow’s effortlessly readable 800-word biography of the man himself hit the shelves in 2004, Alexander Hamilton was the USA’s forgotten Founding Father. But Miranda’s dazzling creation – which let me say from the get-go lives up to every ounce of its hype and then some – doesn’t just eulogise the architect of the US Constitution, by paralleling his life with that of his nemesis, the equally neglected Aaron Burr, it provides a snapshot of the birth of a nation while lauding the value of immigrants who, when there’s dirty work needs doing, as the musical puts it, “get the job done.”

Austin Scott as Alexander Hamilton. Photo © Joan Marcus

Austin Scott as Alexander Hamilton. Photo © Joan Marcus

Alexander Hamilton was just such an immigrant. Born out of wedlock on a Caribbean island, by a combination of domestic tragedy and good fortune, he found himself shipped off and educated in the American colonies. Attached as aide to George Washington for much of the Revolutionary War, he went on to become his fledgling country’s first treasury secretary, established the US Coastguard, founded the Bank of New York, and devised a national financial system so sophisticated that many of its vestiges are still with us today. He may be a prime example of an American Icarus, but his 49-year life was packed with more incident than a man twice his years.

The musical, which literally bursts onto the stage in Thomas Kail’s fluent, fluid production, is imbued with a heady sense of youthful radicals determinedly “not throwing away their shot”, perfectly capturing the zeitgeist and energy of a time when idealism jostled with revolution and anything seemed possible. That it does so through a fusion of hip hop with R&B, pop, soul and a dash of good old-fashioned Broadway show tunes is just one of its marvels. As an utterly compelling musical about constitutional affairs and early-American fiscal policy, it’s well-nigh miraculous. Oh, and if hip hop isn’t exactly your thing, I’d stake my life in a duel that Hamilton will change your mind.

Given the complexities of the late-18th-century political maelstrom, a welcome clarity is one of the musical’s greatest strengths. Miranda has packed his razor-sharp lyrics with more facts and a broader vocabulary than you’ll find in the average encyclopaedia, yet he’s done it with such keen attention to comprehensibility and scrupulous craftsmanship that you emerge two-and-three quarters of an hour later considerably the wiser. His inexhaustible wit and wordplay are a constant delight, bending the speech rhythms of hip hop to his will, yet always with half an eye or ear on a listener’s entertainment.

“I’d rather be divisive than indecisive,” raps Hamilton, delivering a key character analysis in six simple words. “How does a ragtag volunteer army in need of a shower / somehow defeat a global superpower?” says Burr, shining a modern-age mentality on the Age of Enlightenment. “So I’m the oldest and the wittiest, and the gossip in New York City is insidious,” patters out Hamilton’s future sister-in-law Angelica Schuyler. And it goes on, and on, and gloriously on.

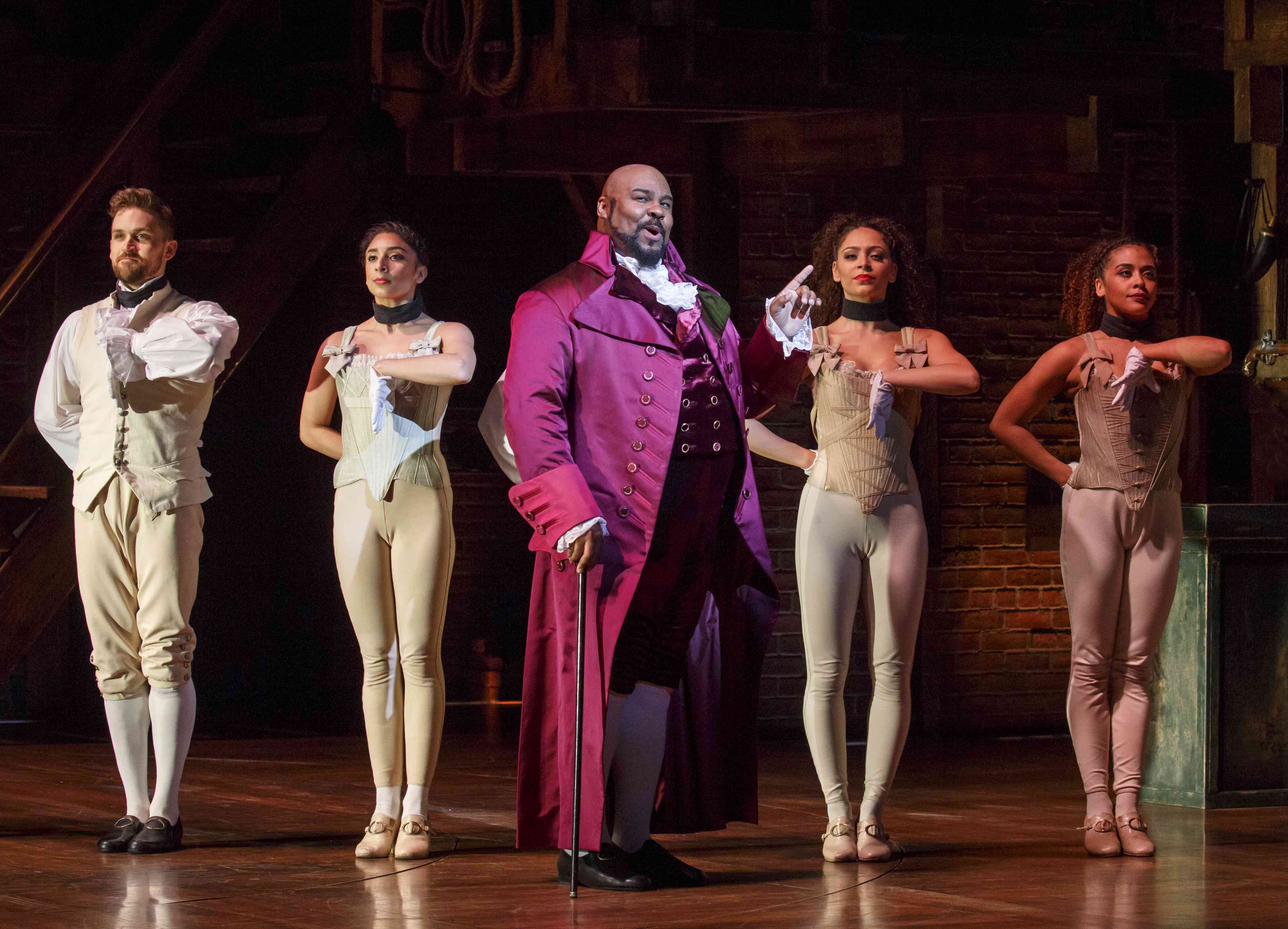

James Monroe Iglehart as Thomas Jefferson. Photo © Joan Marcus

James Monroe Iglehart as Thomas Jefferson. Photo © Joan Marcus

The storytelling is remarkable as well. A number like The Room Where It Happens doesn’t just question how Hamilton managed to get his fiscal plan across the line despite virulent opposition from Jefferson, Madison and a fair proportion of Congress, it neatly encapsulates every politician’s desire to be at the top table. Its modernity reminds us of contemporary goings on behind closed doors, dodgy dealings like the now infamous Trump Tower meeting. The rapped-out Jefferson-Hamilton debates condense complex theories – like the value of a federal government assuming the national debt – into character-revealing bite-size pieces. The Schuyler Sisters doesn’t just introduce us to three independent women who can and do quote the Declaration of Independence, it carries us along on the crest of a wave as we share in the heady thrill of being at the coalface of a revolution. “Look around, look around at how lucky we are to be alive right now!” they sing in a goosebump inducing ensemble. “History is happening in Manhattan, and we just happen to be in the greatest city in the world!”

Like the best historical theatre, Hamilton has a great deal to say about the art of politicking. Nuggets like “Talk less, smile more,” and songs like Washington On Your Side show the seamier side of the art of the political deal, while The Reynold’s Pamphlet, where Hamilton commits electoral suicide to save his public skin by revealing his long-buried affair with the Stormy Daniels of his day, reminds us that nothing has changed (except, of course, that unlike the current incumbent of the White House, Hamilton never used campaign funds to buy off his paramour).

Kail’s unflagging, frequently dizzying staging is deceptively simple with set elements moved by hand around David Korins’ scenic design, a period jewel box of wooden galleries and a central revolve. Endlessly inventive, the helter-skelter sense of a race against time is enhanced by Andy Blankenbuehler’s imaginative, smartly abstracted choreography. Paul Tazewell’s colourful riffs on 18th-century costume do the rest, the whole thing set off a treat by Howell Binkley’s breath-taking lighting. Kurt Crowley’s musical direction is tightly disciplined, yet there’s plenty of air around it to help get our ears accustomed to the torrents of text. Punchy, yet crystal clear, Nevin Steinberg’s sound design has to be one of the finest I’ve heard on Broadway – no wonder it won the Olivier Award in London.

As Hamilton, Austin Scott drips charisma, capturing the man’s endless optimism, pushy arrogance and insatiable appetite for the written word (of the 85 Federalist Papers written over six months to promote the ratification of the US Constitution, Hamilton wrote 51). Dynamic, yet thoughtful, he’s deeply touching in It’s Quiet Uptown as he and his wife struggle to come to terms with the fallout from Hamilton’s affair and the loss of a son. Ryan Vasquez – not that you’d guess, but actually a standby for Daniel Breaker – matched him as Aaron Burr in a magnetically layered performance that charted the proto-politician’s journey from urbane lawyer to opportunistic Vice President. His diction was superb, making his narration of much of the show vividly comprehensible. The moment when Hamilton tips the election of 1800 in favour of his old enemy by declaring that “Jefferson has beliefs, Burr has none,” is masterfully played by all three men.

Mandy Gonzalez, Lexi Lawson and Joanna A. Jones as the Schuyler Sisters. Photo © Joan Marcus

Mandy Gonzalez, Lexi Lawson and Joanna A. Jones as the Schuyler Sisters. Photo © Joan Marcus

Denée Benton (Natasha in the admirable Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812) is enormously sympathetic as Eliza Hamilton, née Schuyler. Her light, high belt conveys the commitment of the woman who would survive her husband by 50 years and go on to found New York’s first private orphanage. It also expresses the fragility of a wife who, after the Reynolds’ Affair, “wrote herself out of his narrative” by burning their letters. As an achingly intelligent Angelica Schuyler, Mandy Gonzalez manages to convey the manifold complexities of a woman who gives up the man she adores for the sister she loves.

Although it isn’t always easy to grasp every French-accented word of James Monroe Iglehart’s Marquis de Lafayette, his preening, self-confident Thomas Jefferson is a masterpiece. Chernow – and hence Miranda – puts a huge question mark over the most ambiguous of the Founding Fathers, yet Iglehart’s puffed-up, smarmy-charmy performance leaves you with a feeling of respect, if not with much fondness. Anthony Lee Medina is an engaging John Laurens, the Hamilton friend who carries much of the show’s abolitionist agenda, while Wallace Smith is a high-octane Hercules Mulligan in brilliant contrast to his round-shouldered, down-in-the-mouth James Madison.

Deon’te Goodman – a standby for Carvens Lissant – exudes calm concern as George Washington, making much of the convoluted surrogate father son relationship between the two men, while a flouncing Euan Morton – last seen, by me at least, as a gender-bending Boy George in the London production of the 2002 musical Taboo – inevitably brings the house down as a pompous, purse-lipped King George III.

Euan Morton as King George III. Photo © Joan Marcus

Euan Morton as King George III. Photo © Joan Marcus

The original show, which won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Drama plus 11 Tonys including Best Musical, Best Book and Best Original Score, will make landfall in Sydney in 2021, and since tickets on Broadway and in London have been notoriously hard to score, keep your eyes peeled for the on-sale date. Hamilton is one of those shows that comes along once in a decade, and that’s if you’re lucky. Take a leaf out of Alexander Hamilton’s playbook, is my advice, and make certain you’re not throwing away your shot.

Hamilton is at the Richard Rodgers Theatre on Broadway

For ticketing information and a waitlist for the Sydney staging, visit the Australian production’s website

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.