The cult 1977 film Saturday Night Fever put the disco phenomenon on the map and made a star of John Travolta, while sales of the soundtrack, which included several numbers especially written by the Bee Gees, went ballistic. It remains the second best-selling soundtrack of all time (behind The Bodyguard), selling over 45 million copies.

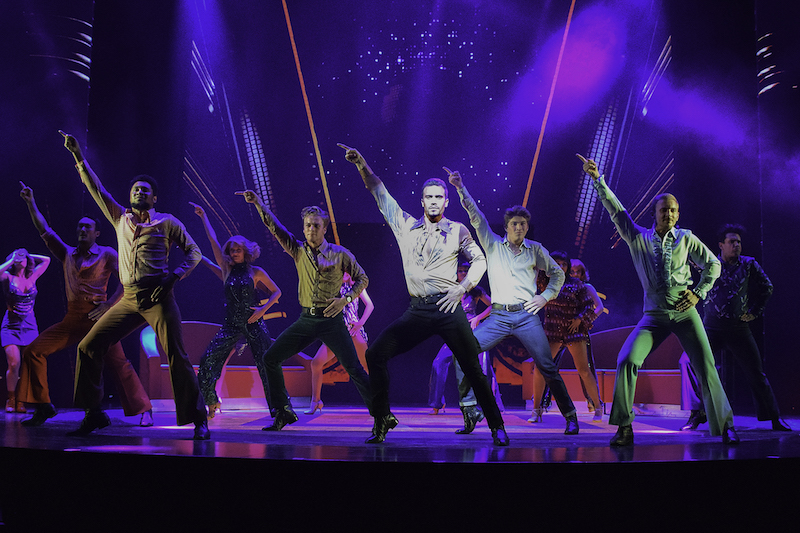

Euan Doidge and the cast of Saturday Night Fever. Photograph © Heidi Victoria

Euan Doidge and the cast of Saturday Night Fever. Photograph © Heidi Victoria

This musical theatre adaptation is a pale imitation, losing the heart, soul and grunt of the film. The dance numbers are the best thing about it, but a thin plot, one-dimensional characters, dialogue scenes that rarely make it out of first gear, and some odd staging, mean there is virtually no emotional connection with what is happening on stage.

The film tells the story of Tony Manero, a working class 19-year-old living in the Bay Ridge neighbourhood of Brooklyn. He escapes from the boredom of his dead-end job in a hardware store by strutting his stuff at the local discotheque each weekend where he is the king of the dance floor. Meeting Stephanie Mangano, who is also a wonderful dancer and determined to improve her own life and move to Manhattan, Tony sidelines his wannabe girlfriend Annette and asks Stephanie to dance with him in a competition at the club where there is $500 to be won.

The story was based on a 1976 New York Magazine article by British writer Nik Cohn, “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night”, about supposedly real people, though Cohn later admitted that he made it up. The musical was first seen in the West End in 1998, adapted by Nan Knighton (in collaboration with Arlene Phillips, Paul Nicholas, Robert Stigwood and Bill Oakes) and directed and choreographed by Phillips, where it played for two years. A Broadway production opened in 1999, and ran for nearly a year and a half, with other international productions following.

This production, directed by Karen Johnson Mortimer, is based on a new version which recently premiered in Paris, reworked by Ryan McBryde and directed by Stéphane Jarny. In an article in the theatre program, producer John Frost says that he saw the French production and “loved it… Cleverly, they’ve cut all the darker elements from the piece which make it more of a family entertainment”.

The plot of the film is pretty faithfully followed but while there is still ugly misogyny, machismo racism and suicide, the sexual violence has been toned down (the date rape of Annette in the car, for instance, is now averted by Tony) and obscenities reduced. All the humanity, authenticity and emotional subtlety has disappeared too. The dialogue scenes feel perfunctory, added just to tick off each plot point in order to move on to the next dance number.

Marcia Hines. Photograph © Heidi Victoria

Marcia Hines. Photograph © Heidi Victoria

The show begins with a clock ticking backwards from now to the 1970s as Stayin’ Alive kicks in. With dancers in glittery costumes taking to the stage in front of a drape and disco balls, it feels more like the start of a contemporary casino show than a return to the working-class world of 1970s Brooklyn.

The Bee Gee songs and other disco numbers are sung for the most part by a strong quartet of singers – Paulini Curuenavuli, Natalie Conway, Bobby Fox and Nana Matapule, who are frequently placed to the side of the stage like a kind of disco Greek chorus. They all produce the goods vocally, but it feels rather weird to have Fox wandering through the dance studio singing More Than a Woman, while Tony (Euan Doidge) and Stephanie (Melanie Hawkins) dance.

The biggest hits of the night come from Marcia Hines as The Diva, who shows how disco should be sung and exudes the kind of presence that the show has been crying out for with Disco Inferno and You.

Given that the two central characters don’t have any big numbers of their own, it is strange that two supporting characters – Annette and Bobby (who has got his Catholic girlfriend pregnant) – both have solo moments. As Annette, Angelique Cassimatis sings If I Can’t Have You, and Ryan Morgan as the increasingly desperate Bobby sings Tragedy. Both do a good job, but the songs don’t have the impact they would have were the show structured differently and we had got to know the characters better.

Staging-wise, it feels as if ideas from several different productions have been somewhat clunkily brought together. The set uses digital screens, with images of the freeway, road signs and train stations creating a real touch. Then we have cheesy shots of dark clouds swirling past for Tragedy. The decision to only portray Tony’s parents on a large screen – seen at an inflated size and seated at a table talking to Tony, while Doidge stands on the stage below, next to a dark drape looking up at them – is bizarre. One can only assume it was to make scene changes easier, but there’s no way on earth those scenes can ring emotionally true, not helped by the incredibly broad accents used by Denise Drysdale and Mark Mitchell.

The appearance of Bobby’s ghost – played by another actor (Stephen Perez) rather than Ryan who plays Bobby – dancing in a white suit is another oddity, and a distraction from the real heart of the scene, which is Tony, sitting on the train (much further back on stage), devastated at all that has occurred.

The costumes are also a bit of a mish-mash; some clearly reference the 1970s while other look more like blinged-up nightclub outfits from today. Doidge, meanwhile, wears tight black jeans that look decidedly contemporary; where are the wonderful high waist, flared trousers that Travolta wore? (The white suit makes an appearance of course). What’s more, one ensemble member was wearing trousers that were obviously the wrong shape and too big for him, and clearly tacked together at the back of the waistband, which just looks tacky.

Melanie Hawkins and Euan Doidge. Photograph © Heidi Victoria

Melanie Hawkins and Euan Doidge. Photograph © Heidi Victoria

Neither the direction nor the staging help the performers, most of whom struggle to give the sketchy dialogue scenes any real life. It goes without saying that Travolta is a tough act to follow for anyone playing Tony, particularly when you don’t have the close-ups that the camera allows. Doidge and Hawkins both dance well but aren’t able to convey the vulnerability, insecurity and emotional confusion going on beneath the surface as Tony and Stephanie. Other characters are given little chance to shine but the performers do what they can.

The one thing that fires is the choreography by Malik Le Nost. The dancing from the excellent, committed ensemble is sharp and slick – though everyone dances so well that Tony, supposedly the best dancer by a mile, doesn’t stand out from the crowd, other than by being centrally placed. Nonetheless, the dancing is where the production does have some real energy and joy, particularly the scenes when everyone dances in tight unison. With the music pumping (terrific work from musical director David Skelton and his eight-piece band) the production takes off. It’s a shame the dark, gritty emotional life of the show doesn’t take off too, as it did in the film. But in the end, this musical is all about the upbeat song and dance.

Saturday Night Fever plays at Sydney’s Lyric Theatre until June 2

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.