It begins and ends with a parent begging for the return of his child, crossing enemy lines in order to do so. This is Homer’s epic poem The Iliad, presented as part of Sydney Festival in a sovereign adaptation by actor and director William Zappa. Performed in three parts with a total runtime of nine hours, The Iliad Out Loud embraces all the joyful and bitter shades of human experience, bringing us round the campfire once again.

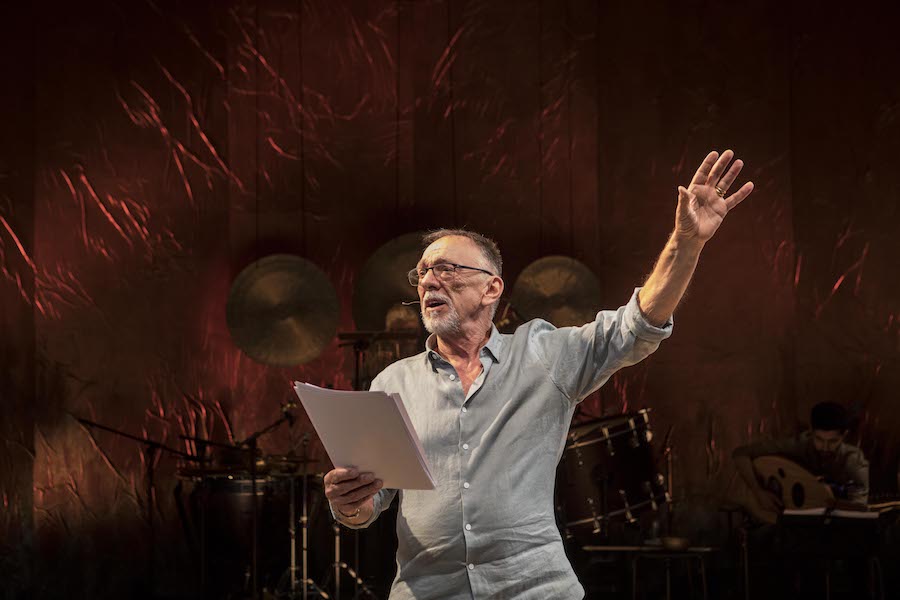

William Zappa in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Lisa Tomasetti

William Zappa in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Lisa Tomasetti

Drawing on 17 translations and the expertise of classicist Elizabeth Minchin, Zappa’s adaptation has been seven years in the making. Befitting its monumental nature, audiences had the choice of seeing it over three consecutive nights or the course of a day, beginning and ending at 10 o’clock. This reviewer chose the marathon option, taking a headlong plunge into a world of unremitting violence and tenderness, petty feuds and principled stands.

Although bearing sheafs of paper, Zappa (who also directs, assisted by Damien Ryan) and his fellow storytellers Blazey Best, Heather Mitchell and Socratis Otto slip in and out of Homer’s myriad characters with extraordinary facility. You never see them sweat, but they do flex every acting muscle possible in order to guide us through the long, bloody sweep of the Trojan War’s final weeks. All take turns playing narrator as well as a number of principal roles, this last having a particularly intriguing effect when it comes to the gods of the story. Presenting multiple versions of the same deity onstage gestures not only to the many ways in which they have been interpreted over time, but also the proliferation of sources and voices that contributed to the fashioning of The Iliad. This intentionally diffuse approach is one that really works.

Socratis Otto, Heather Mitchell and Blazey Best in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Lisa Tomasetti

Socratis Otto, Heather Mitchell and Blazey Best in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Lisa Tomasetti

The action takes place on a circular disc of sand, configured differently in each part to represent first Troy, then the spiked trench outside its walls, and finally a burial mound. The storytellers are joined onstage by percussionist Michael Askill and oud player Hamed Sadeghi, who call the audience to attention, underscore the action and ratchet up moments of narrative tension to brilliant effect. The foiled backdrop and atmospheric lighting by Matt Cox gives the production a flavour of antiquity, as do the actors’ blue and black modern dress and bare feet.

Zappa naturally speaks the text with greatest authority, rhythmically incisive and always perfectly pitched, whether embodying an ornery Zeus, broken-hearted Priam or mourning Helen. He anchors the production, and his turn as Priam is rightfully heartrending. Best is an energetic, vivid narrator, and while she flits between a dizzying number of roles with ease, her Andromache is most powerful of all, desperately aware of her fate and that of her son’s if Troy is lost. As usual, Mitchell brings gravitas and ready wit to proceedings, making for an ideal Odysseus in The Embassy to Achilles – an iron fist in a velvet glove – and an entertainingly earthy, scheming Hera. She’s also note perfect as a grieving Hecuba, and you buy that, as Homer tells us, this is a woman who has torn the hair from her own head in anguish.

Zappa in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Jamie Williams

Zappa in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Jamie Williams

Otto has the unenviable task of portraying narrative giants Achilles and Hector, but very much rises to the challenge. He brings subtlety to these showy roles, emphasising their shared values and very human qualities. Otto is especially moving in Hector’s farewell to Andromache, and foregrounds the questing intelligence of Achilles, most obvious in the thoroughly reasoned way he refutes Odysseus’ arguments and Agamemnon’s bribes in the Embassy scene. Although there were recurring sound issues, the cast coped admirably and did not let it become a distraction.

The staging is simple, but full of the kinds of gestures or props that evoke worlds. Certain passages are very much elevated by being transplanted to the stage, as with the Catalogue of Ships that closes Book Two. Very much what it says on the tin, even the most devoted reader might find themselves skating over this section in The Iliad. Here, the tense musical underpinning and chorus-like intoning of the refrain “sleek dark ships” is both mesmerising and thrilling, powerfully evoking the Greek reinforcements converging on Troy.

Zappa’s adaptation is a lively one, infused with just the right amount of modern Australian to tickle the ear – a judicious “fucking” is one such example, paying dividends when delivered by Mitchell in unmistakable ocker. Yet he has also ensured that it retains the lyricism of Homer’s original, and with it a sense of occasion, of louring clouds and the noble but ultimately futile struggle of the individual against destiny. Zappa has made logical excisions that few would miss (i.e. the night mission of Dolon, a truly outlandish bit of writing), and the pacy compactness of the adaptation’s first part is especially worth praising.

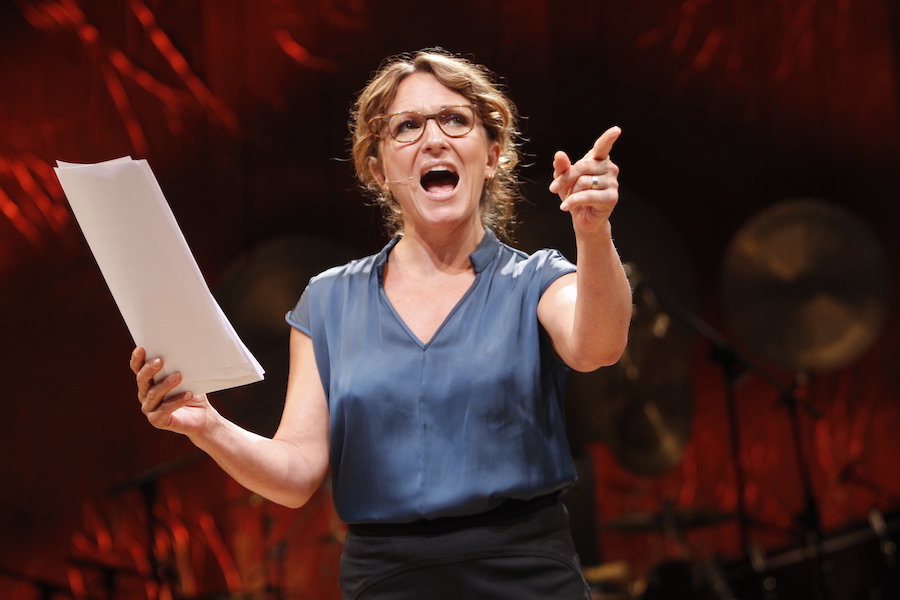

Best in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Jamie Williams

Best in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Jamie Williams

But what impresses most of all is Zappa’s handling of war. Verging on the baroque in their intensity, Homer’s many descriptions of battlefield deaths are given full justice here, underlining just how much war impoverishes the human spirit. Zappa’s adaptation and production understands this intuitively, as when Patroclus taunts the corpse of a man he’s just killed. Having struck him with a stone, his victim is described as vaulting off his chariot “like a diver” – as Patroclus, Blazey gives the young warrior no hint of honour in this moment, no insight into why he is so beloved of Achilles. Instead, he jeers like a brute, cackling as he says that in life the Trojan would have had no trouble diving for oysters. Here Zappa powerfully drives home the point that in war men lay waste not only to their enemies but their souls as well, and remembrances of a peacetime world are warped beyond recognition into metaphors of carnage.

Zappa, Best, Otto and Mitchell in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Lisa Tomasetti

Zappa, Best, Otto and Mitchell in The Iliad Out Loud. Photo © Lisa Tomasetti

His adaptation handles just as masterfully the extremes of human grief in Homer’s Iliad. Such instances are treated with a matter-of-factness appropriate to a world steeped in so much blood, as when Priam begs Achilles to return Hector’s body to him. When the old king reports that not only has he wept constantly since Hector’s death, he has also rolled himself in shit in a fit of despair, Zappa speaks the line as if there is no other response available to a father who has witnessed the desecration of his son’s corpse.

Homer takes our breath away in these final moments of The Iliad. Priam’s grief is matched by the sorrow Achilles feels for dead Patroclus, and in a shining moment of tenderness,“both men weep”, Zappa tells us. The economy of these words are a gut punch. Achilles grants Priam’s request, and the story ends not with further recrimination but with Hector’s burial, Homer and Zappa showing us the precious, too often squandered, gift of mercy.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.