Dock Street Theatre, Charleston

June 7, 2018

While classical music still finds room for plenty of commissions, one of a creator’s knottier problems is securing that often elusive second performance. A credit to Charleston’s enterprising Spoleto Festival then for taking up Australian composer Liza Lim’s challenging Tree of Codes two years after its well-received Cologne premiere. And not just a new production – George Street’s Zero Restaurant has even designed a craft cocktail: Mixologists take note, the Two Worlds in Thyme blends rum, thyme-infused Aperol, lemon and oleo saccarum (that’s a syrup of citrus peel and sugar) with an egg-white foam. Delicious!

Elliot Madore and Marisol Montalvo in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Elliot Madore and Marisol Montalvo in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Knotty and delicious are two words that could equally be applied to Lim’s opera. Tree of Codes takes as its basis Jonathan Safran Foer’s book of the same name, but Bruno Schulz, Goethe and Foucault also form important source material. Foer’s text is an artwork masquerading as a book. Taking a copy of Schulz’s Street of Crocodiles, the American author literally excised the vast majority of the Polish writer’s original words in order to carve out a new story, leaving a filigree patchwork of text floating over empty spaces through which the reader can glimpse other possibilities for stories buried deep inside. Even Foer’s title was Schulz with the scissors taken to it (sTREEt OF croCODilES).

Schulz’s 1934 original recounts fragments in the life of a merchant-cum-inventor and his family, full of dreamlike events, crazy science and visionary experiences. ‘The Father’, now apparently deceased finds his way into Foer’s artwork, as does his inquiring young son, whose quest to find (and ultimately sublimate his missing parent) becomes a crucial part of Lim’s opera. “Tree of Codes takes place during an extra day grafted on to the continuity of life,” writes Lim in her program note. “Within this margin of secret time, a ‘backstage’ area, the boundaries between the natural world, animals, birds, humans, and machines are dissolving. Dead matter is combined with the living and becomes animated. It learns to dream, to speak, to sing…”

Elliot Madore and Marisol Montalvo in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Elliot Madore and Marisol Montalvo in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Accordingly, Lim’s opera constantly inhabits a wafer-thin line between past and present, hovering somewhere between life and death, between reality and dream, filled with birdsong and sounds reflecting the passing of time. Her orchestra of 17 includes ‘exotic’ percussion, electronics, musical toys and unconventional use of traditional instruments. Musically, it’s a highly attractive score – though rarely conventionally tonal – with some standout set pieces like the story of the two-headed birds sung over pizzicato strings and tuned percussion.

Dramatically, however, it can be an elusive work – I heard Romeo and Juliet mentioned by one audience member, Waiting for Godot by another – which for all its musical appeal clearly flummoxed many in the gratifyingly well-filled theatre. Perhaps it is best appreciated without attempting to grasp any fleeting logic (though there is plenty to occupy the intellect and imagination. In other words, if you go with the flow, Tree of Codes has much to offer, especially in director Ong Keng Sen’s visually sumptuous and well-sung production.

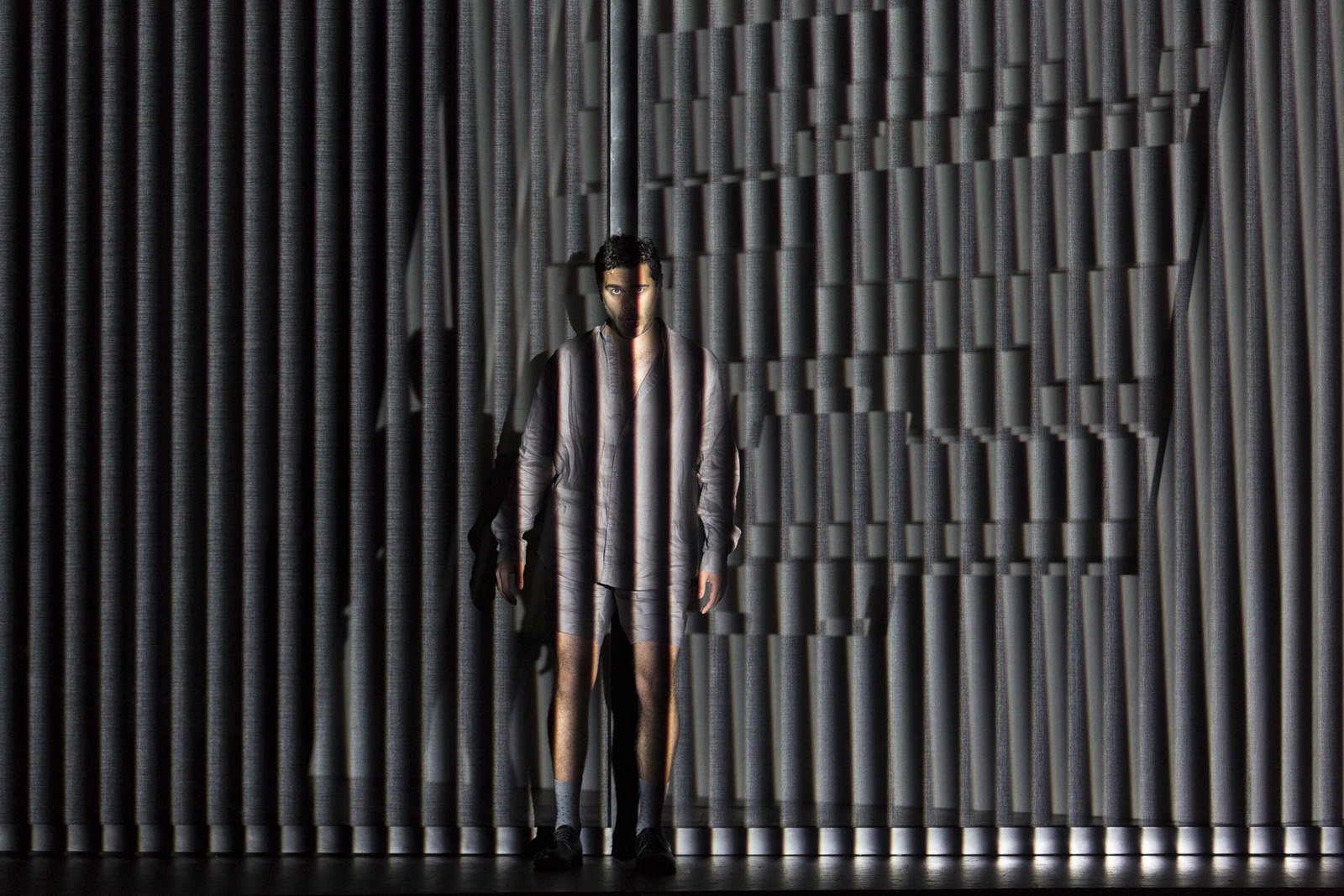

Elliot Madore in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Elliot Madore in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

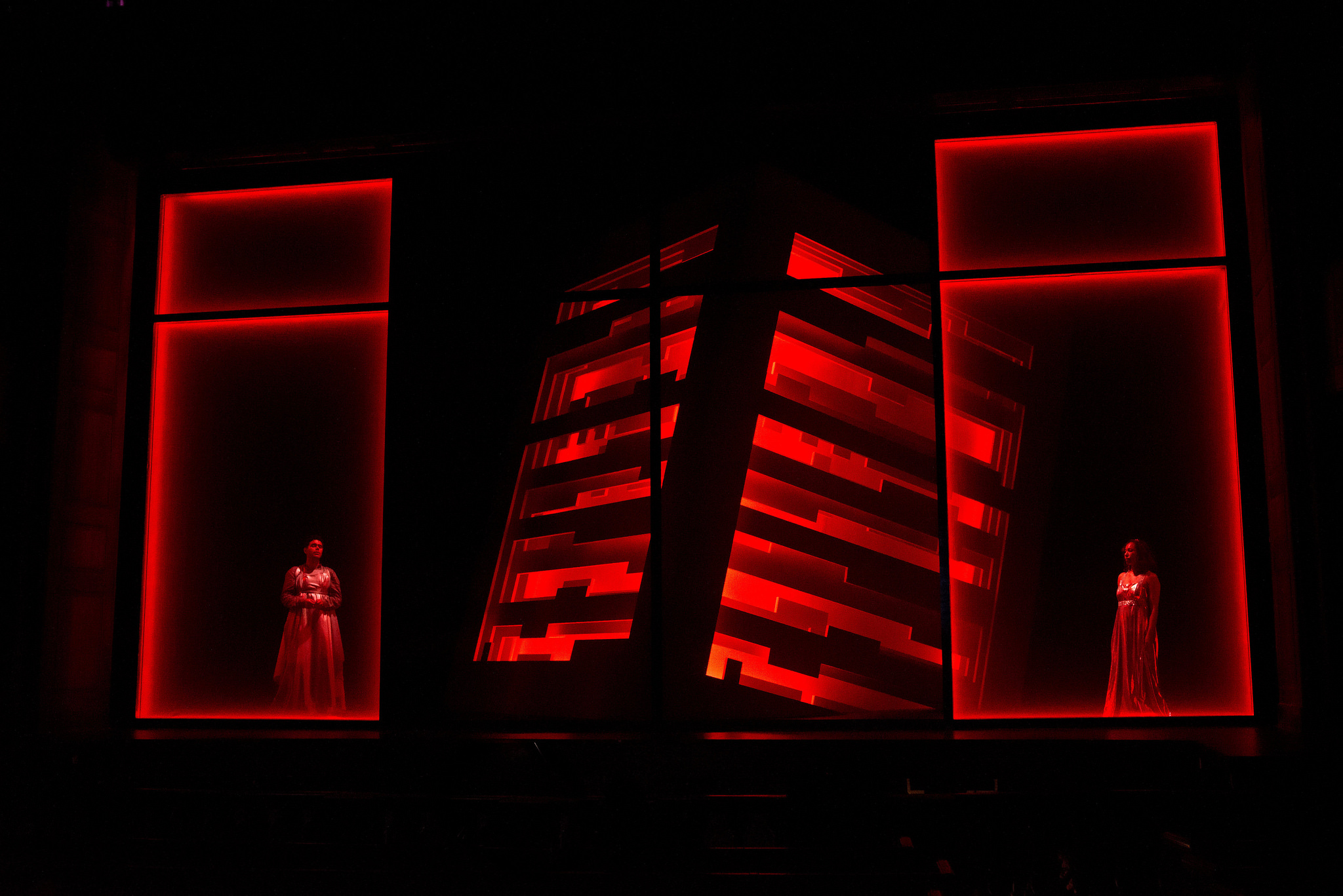

Where the premiere production took an ecology versus science approach, firmly focused on the hybrid “crustaceans, vertebrates and cephalopods” of the father’s mad experiments, Ong goes back to the work’s roots and Schulz’s Jewish narrative of the pre- and post-World War II eras. The action is played out on a stage dominated by a monolith that reflects The Nameless Library, Rachel Whiteread’s Holocaust Memorial in Vienna’s Judenplatz – a sculptural building made up of books with unreadable titles. “Whiteread created sculptures of negative space where she cast the volume of entire houses and rooms, which she termed ‘mummifying the air in a room’,” writes Ong, “These giant sculptures often contained traces of the original room, evoking ghosts and memories of that space. Our colossal monolith evokes Foer’s book, which is itself a negative space of Schulz’s.”

Elliot Madore, Marisol Montalvo and Walter Dundervill in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Elliot Madore, Marisol Montalvo and Walter Dundervill in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Memorial and memory thus play as important a role as the evolution of sons into fathers, another dominant element that culminates in a passage from Goethe’s Erlkönig, Lim’s fractured orchestration evoking Schubert without ever direct quotation. In Tree of Codes, Goethe’s portrait of the father bearing his dead son becomes a mirror image of Foer’s son’s acceptance of his dead father, an element poignantly conveyed in a splendidly committed performance by Elliot Madore, whose warm baritone and excellent diction negates any need for surtitles – always frustrating in an opera written in English. He negotiates forays into head voice and other EVT effects with style, just about triumphing over a rather nerdy pair of schoolboy shorts.

Madore is ably partnered by Marisol Montalvo as the enigmatic Adela character – a combination of guru, siren (seductive and almost Kundry-like at times) before transforming into a figure reminiscent of Guanyin, the East Asian bodhisattva of mercy. Her rich soprano is a little less ideal for delivering clarity of text, but she has an attractive instrument, which flourishes nicely above the stave when pressed by Lim’s captivating imitations of birdsong. The third player, actor and costume designer Walter Dundervill, performs the function of dresser and re-arranger of stage furniture, much like the Kōken in Noh theatre. Ong gives him much to do – at times it feels like too much – and while he carries it off with presence and efficiency, there were times when he changed Montalvo’s costume so frequently it really was impossible to follow the import of the moment.

Elliot Madore and Marisol Montalvo in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Elliot Madore and Marisol Montalvo in Tree of Codes at Spoleto Festival © William Struhs

Whether the audience entirely ‘got’ Tree of Codes, to judge from the post-show chit-chat they clearly did get the spectacular ‘monolith’ set and scrim that carries off both light and video effects like a model on a catwalk. Designer Scott Zielinski is ably abetted by James F. Ingalls lighting design and Austin Switser dazzling video projections. Equally impressive is John Kennedy’s marshaling of the eclectic musical demands of Lim’s score. His 16 players – mostly young – put on a bravura show that even requires them to form a vocal chorus in a couple of places, and while it would be unfair to single any one out, a series of fine horn solos were worthy of particular mention as was the solo flute, required at times to sound more like a shakuhachi.

One of Australia’s most important cultural exports, Lim was clearly delighted that her opera was capable of spawning such totally different directorial responses in its first two stagings. It will be interesting to see if an Australian company or festival might take it up as there is still much to explore in this intriguingly enigmatic and oddly compelling work.

The 2019 Spoleto Festival will run from May 24 – June 9. Programming will be announced in January 2019

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.